The Power of Press Photos

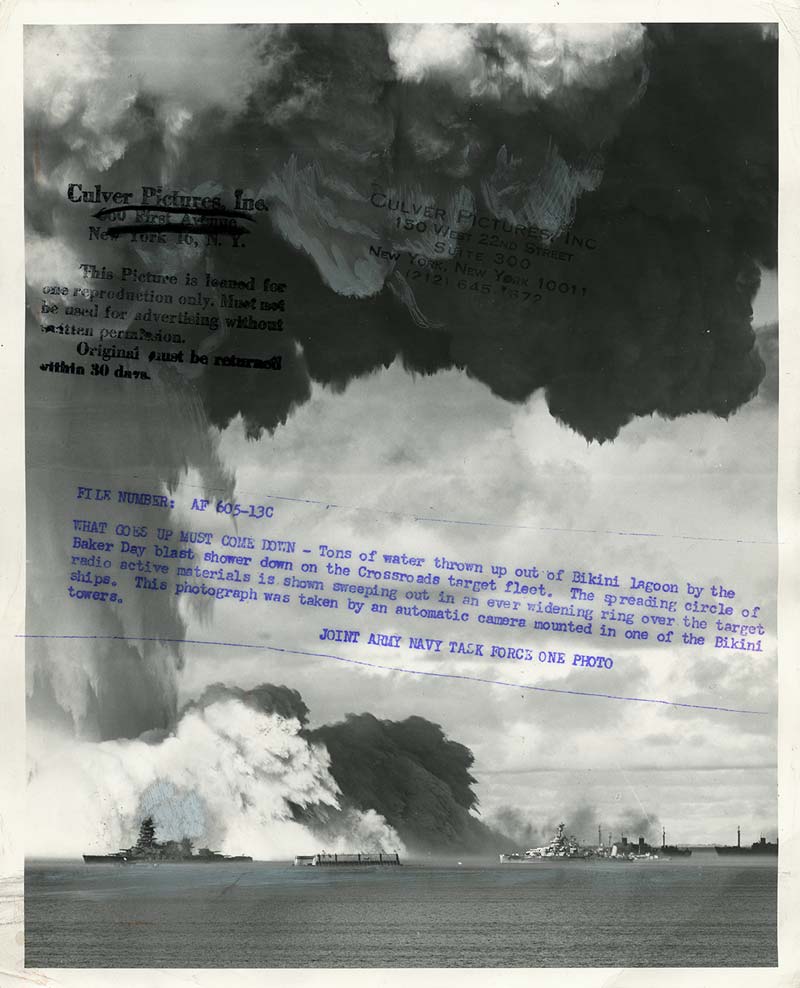

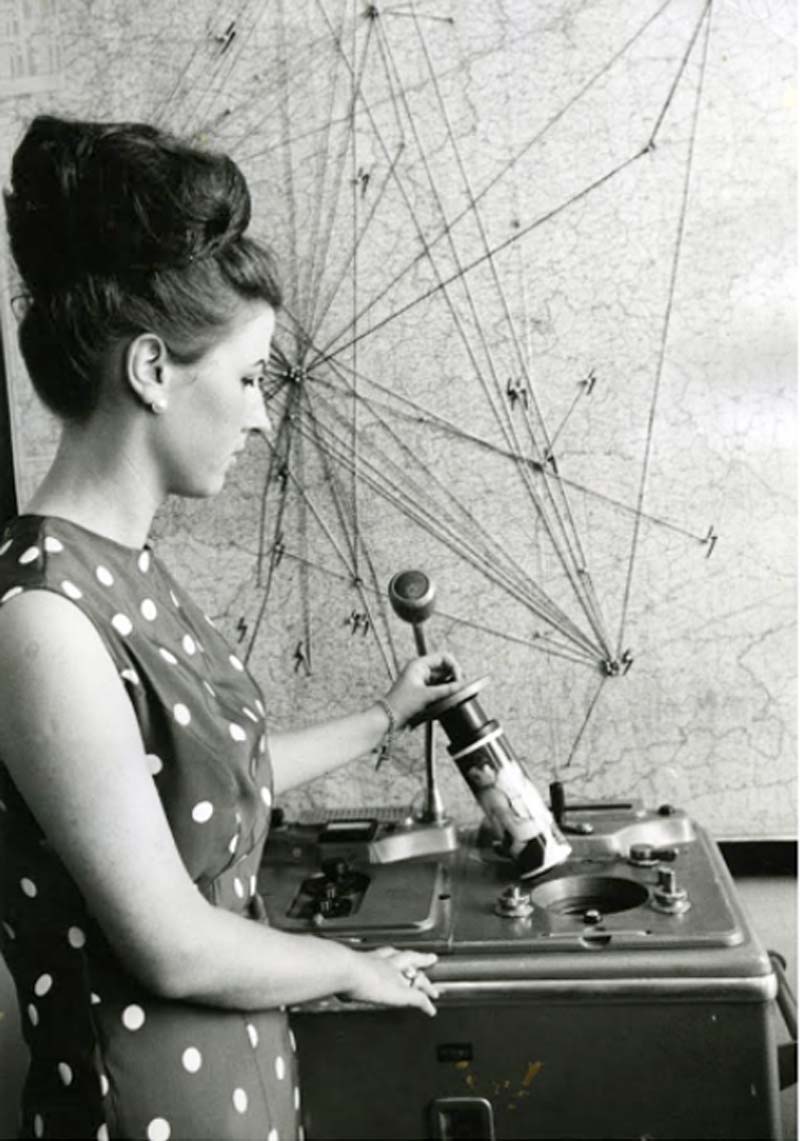

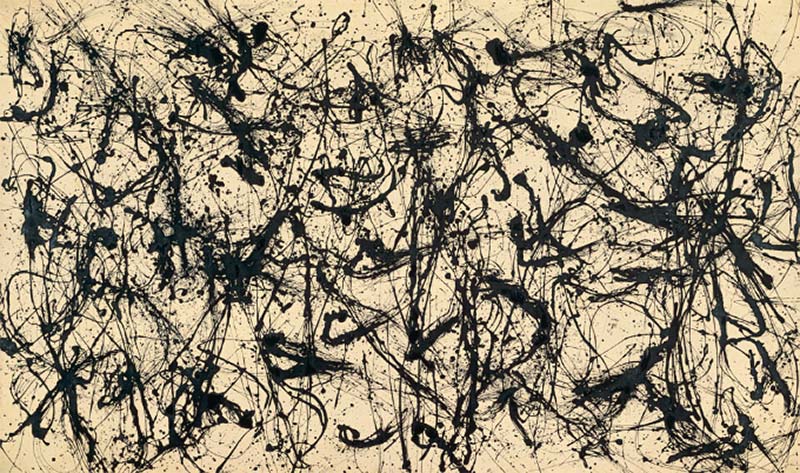

Where do we use photos?

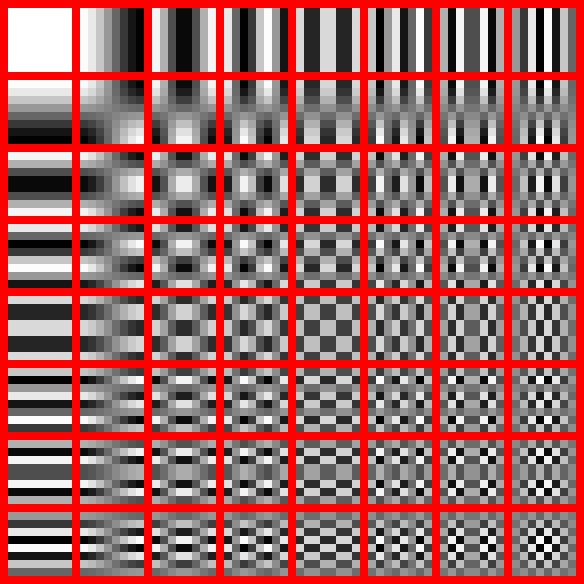

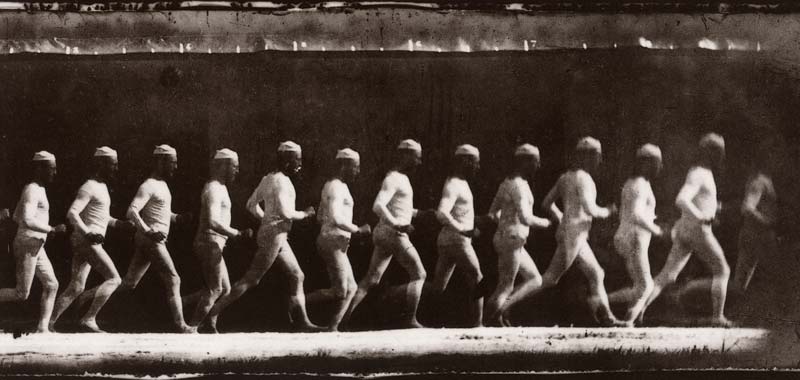

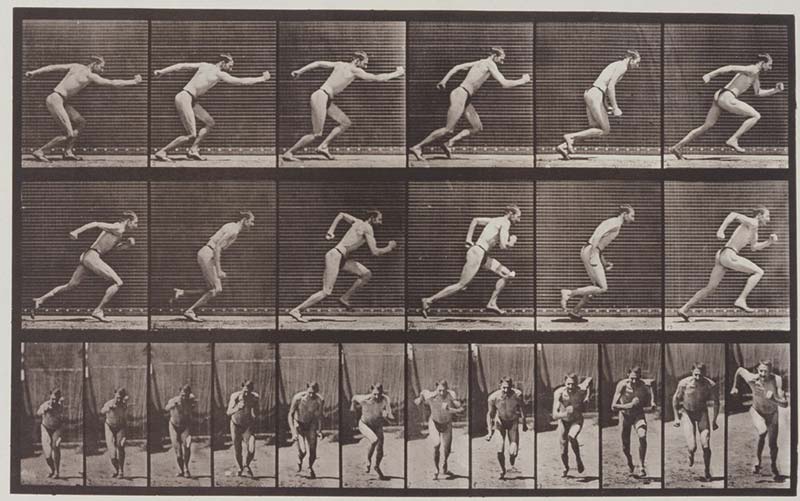

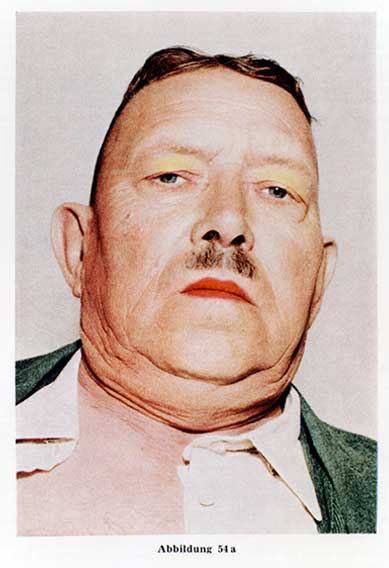

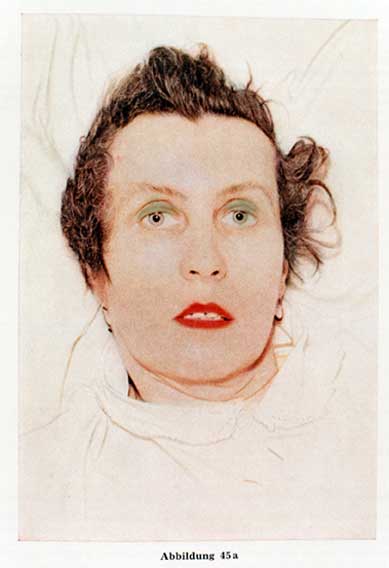

What happens when photos are printed?

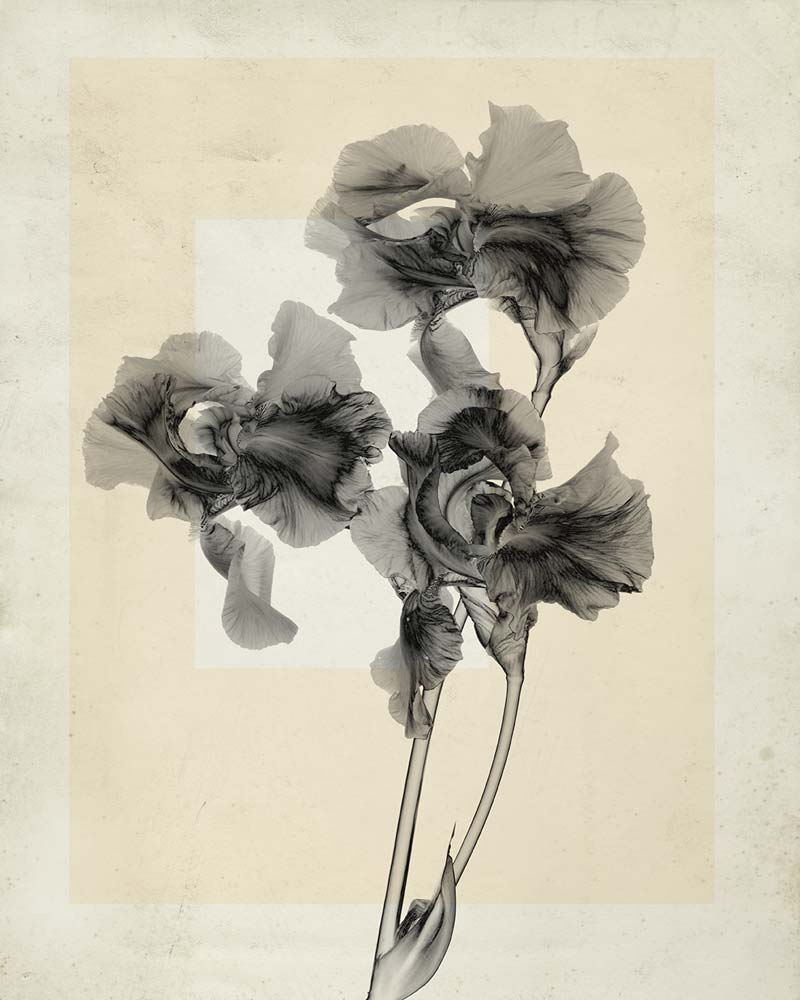

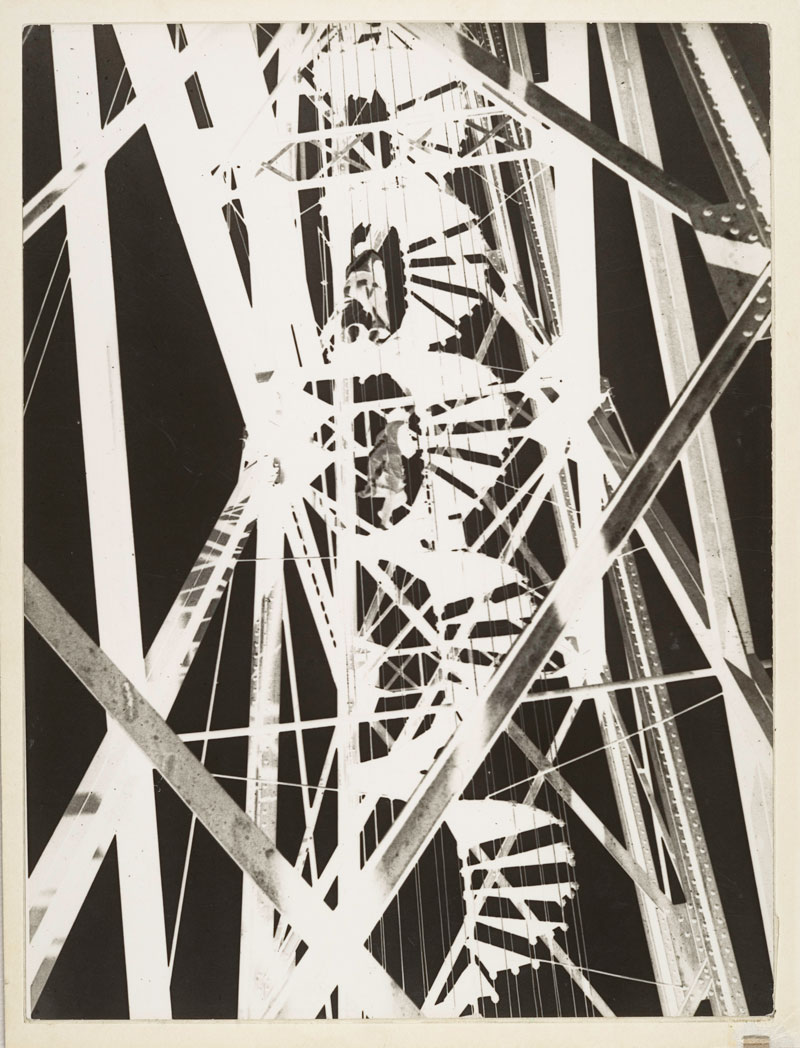

How do aesthetics and statements change?

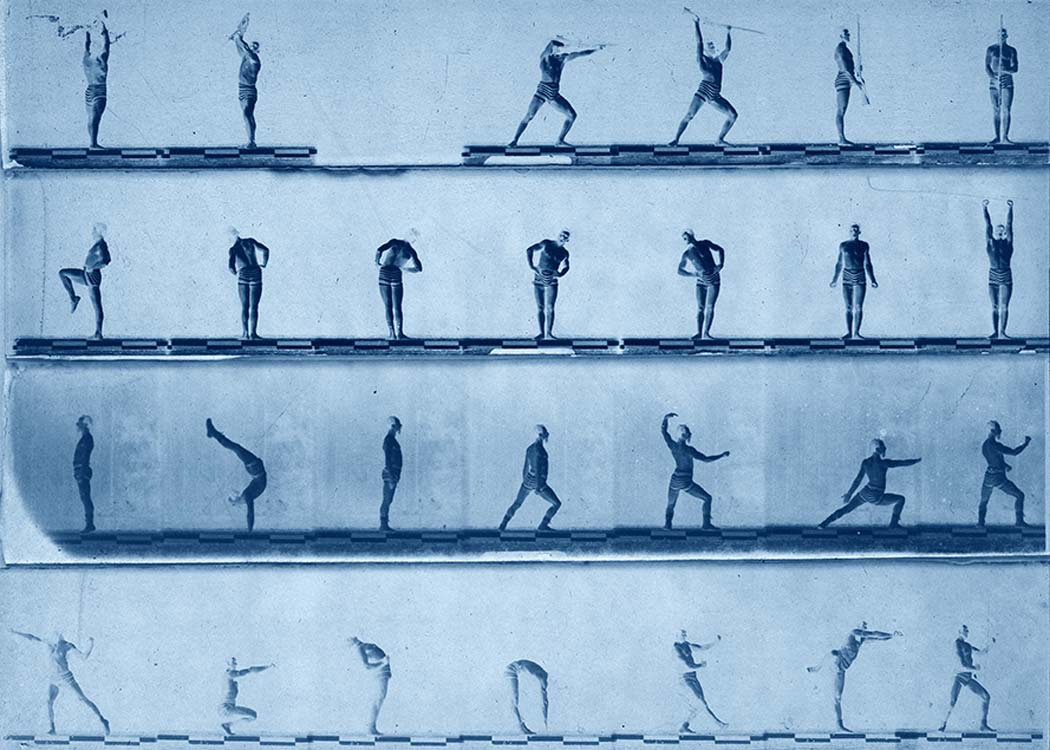

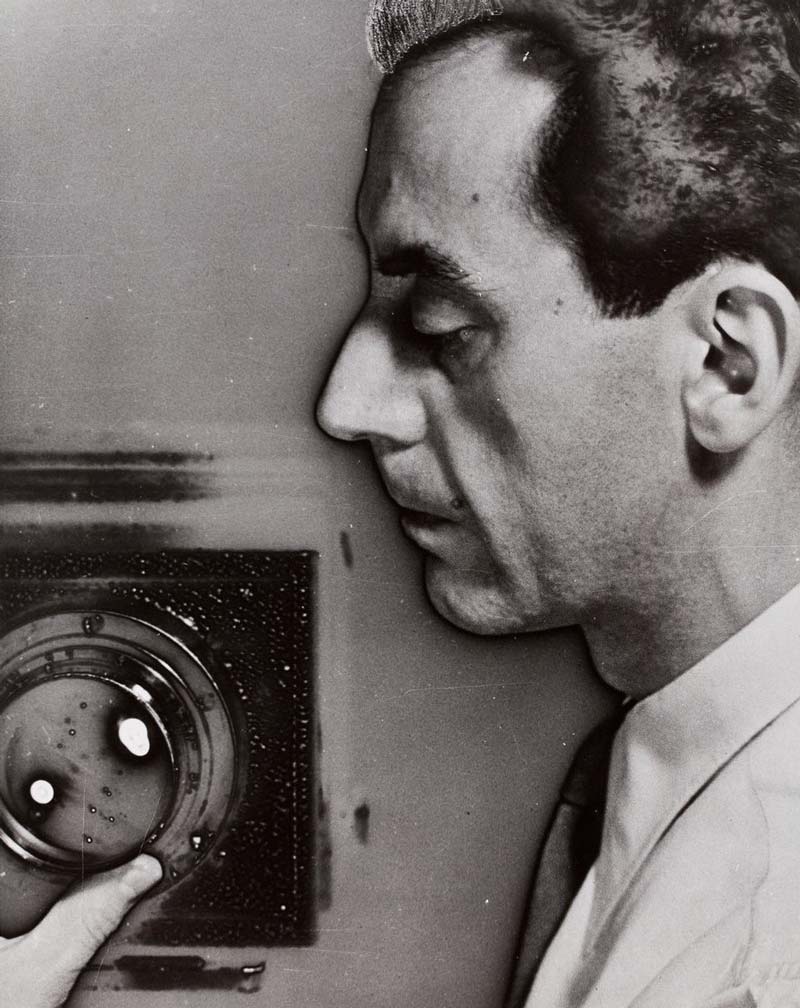

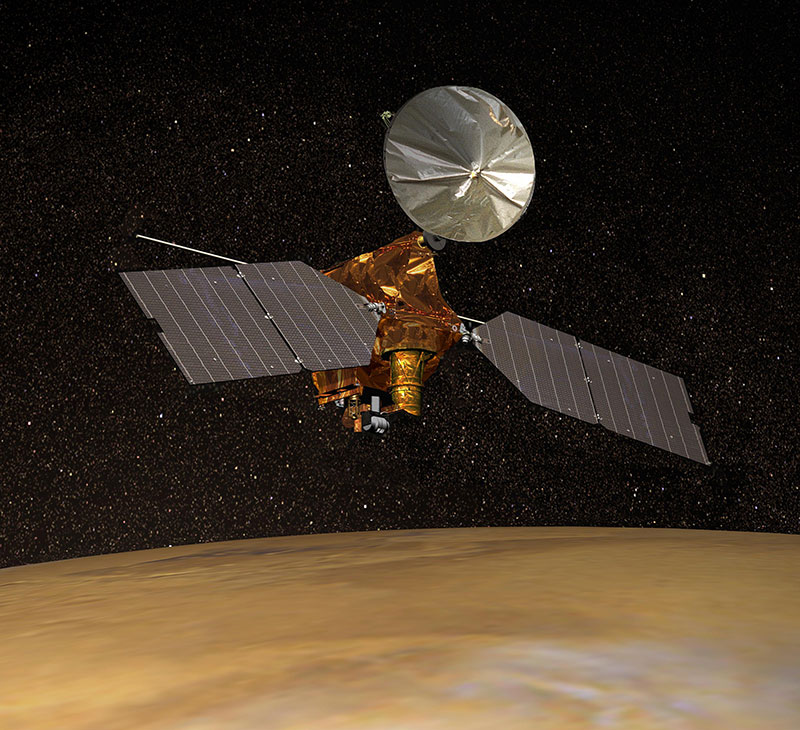

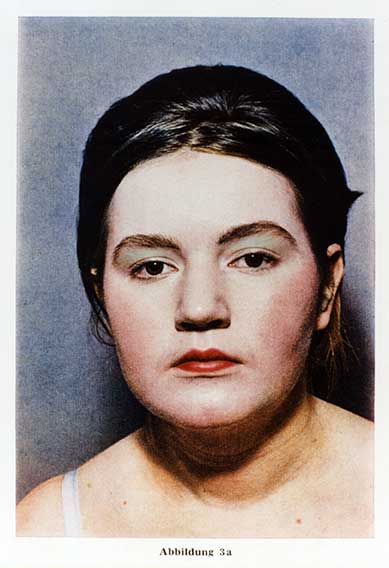

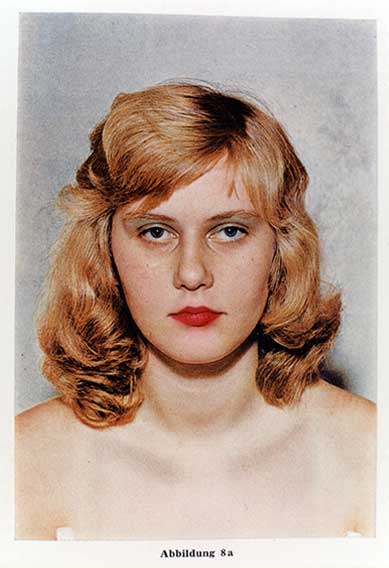

The artist explores these questions in various series, in which he draws on image material from other photographers, processes this, and thematizes contexts. For his series “Zeitungsfotos”, the artist collected and processed newspaper photos to test the familiarity with the motifs and their reliability as carriers of information. In the series “press++”, he reveals the work traces of newspaper staff in conflict with the photos that were taken especially for use in the newspaper. In his new series, “Tableaux chinois”, he examines the use of photographs in political propaganda and reveals the artistic stylization of the photos with reference to the feasibility and time-related aesthetics of the printed products.