Acquisitions

The following pages document what the Freunde der Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen are particularly proud of: the works of art acquired over the years for the Kunstsammlung.

The Freunde do not pursue their own purchasing policy. Instead, they are always merely an “accomplice” of sorts with regard to financing. The purchase is generally preceded by an express wish from the director of the Kunstsammlung to include a specific work by an artist in the collection. Since 1993, the works of art acquired have remained the property of the Freunde. They are made available to the Kunstsammlung on permanent loan without any restrictions.

The “Stiftung Junge Kunst” (Young Art Foundation) administered by the Freunde proceeds in exactly the same way. After the gallerist Helme Prinzen had bequeathed the majority of her assets to the Freunde der Kunstsammlung in 2002, this foundation was deliberately established under a neutral name in order to facilitate donations from other private individuals. Its primary task is the acquisition of art from young artists for the Kunstsammlung.

-

Neel, Alice

The Great Society, 1965Alice Neel is a key representative of American realism. She worked mainly in portraiture. “The Great Society” is one of the few examples in her oeuvre of an anonymous and multi-figured painting. Neel depicts a group of elderly, disillusioned figures over a cup of coffee in Stanley’s Cafeteria, a low-cost café on Broadway, not far from Neel’s home on the Upper West Side. Commenting on American society, the title refers to the 60s U.S. government reform program fighting poverty. The private scene in a public space shows a state of desolation forming in society that no political reform efforts can affect. “The Great Society” is an extraordinary painting in which Neel visualizes her subjective view of a certain socio-political Zeitgeist.

-

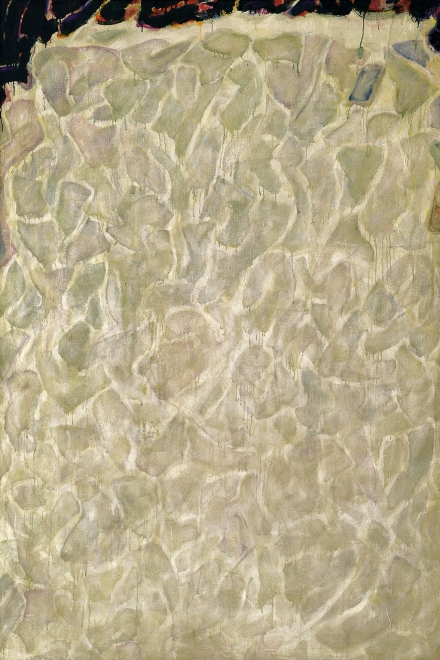

Park, Seo-Bo

Écriture No. 11-77 (Writing No. 11–77), 1977The painter Park Seo-Bo (b. 1931 in Yecheon, Gyeonsang) is among the most important protagonists of Dansaekhwa (monochrome painting) in South Korea. In the 1970s, this group of artists formulated—in dialog with the traditions of Asian philosophy and calligraphy—their response to the abstract painting of Europe and North America. Park Seo-Bo’s art is “based on the idea of totality (under the aspects of time, space, and material),” with which he expounds his relationship to the world. He has been creating the monochrome paintings he calls Écritures since 1967: With a steady, often circular movement, he “writes” with the pencil into the still wet layer of paint. The traces/lines cross each other, at times canceling each other out, while new lines emerge. They ultimately bear witness to the uninterrupted, highly concentrated painting process. For Park Seo-Bo, this quiet, energetic art is a “tool for spiritual development.”

-

Ai Weiwei

Stacked Porcelain Vases as a Pillar, 2017The exhibition of works by the Chinese artist Ai Weiwei presented at the Kunstsammlung in 2019 visualized the basic principle of his artistic practice: “Everything is art. Everything is politics.” Numerous works—including the expansive installation Laundromat (2016) comprised of thousands of articles of clothing left behind in refugee camps—address themes such as displacement, flight, and migration: an issue of dramatic topicality that runs like a thread throughout human history.

Such themes are always accompanied by war, destruction, perilous journeys, and quartering in camps. For Stacked Porcelain Vases as a Pillar, Ai Weiwei translated such traumatic experiences into images “narrated” in the traditional aesthetic of Chinese porcelain painting on the voluminous bellies of six vases stacked on top of each other; an uncompromising inventory of the misery of human migration in the guise of precious, decorated, fragile porcelain vessels.

The work acquired by the Freunde der Kunstsammlung in 2019 complements the collection of works by Ai Weiwei which the Kunstsammlung was able to purchase or—like the work Laundromat—received as a gift from the artist.

-

Richter, Gerhard

Mauer, 1994Since 1960, Gerhard Richter has been painting not only photographic images, but increasingly also abstract pictures, large-format compositions in which manifold possibilities of non-representational painting are brought to light. The title of some of these paintings point back to the objective world, including the small group of Wall paintings (1984, 1994, and 1998).

Dominated by powerful red tones, the canvas from 1994 actually confronts the viewer like a wall. Uniformly placed vertical lines in the partially torn open layers of paint are reminiscent of densely placed shuttering boards that allow only a few glimpses into the depth of the pictorial space. Five years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the title of the painting also evokes associations with the years that moved the Federal Republic.

This outstanding painting was donated by Viktoria von Flemming to the Freunde der Kunstsammlung in 2019, on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the Freunde.

-

Genzken, Isa

Untitled, 2015Reflective metal foils in various colors are glued to the surfaces of four steel panels hanging in a row. This dialog of blue, gold, and silver foils with the picture support evokes associations with the reflective façades of modern high-rises, as well as with packaging materials and modern design. The artist’s connection to architecture in her works is as evident as her fascination with reflective materials that simultaneously open and close the respective space. The boundaries between the pictorial elements and the mirrored exterior space collapse.

-

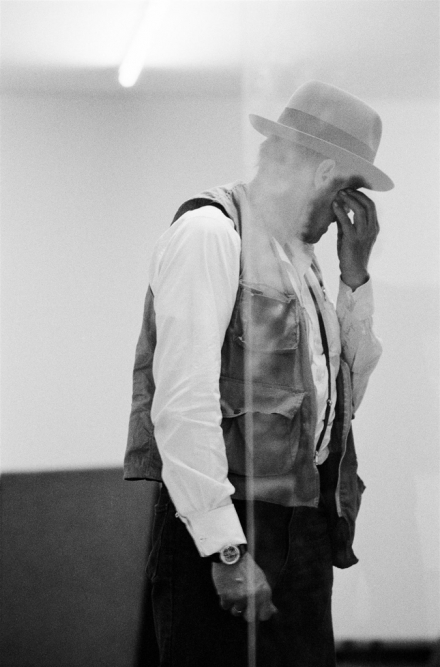

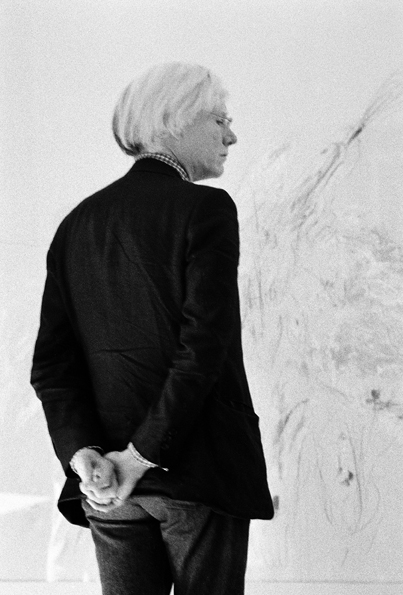

Katz, Benjamin

Artist portraits, acquired in 2018“Something had to happen to make me think that it was worth taking a picture. A situation, a connection, a conversation, an encounter...” A lot has happened: In thousands of photographs, the Belgian-born photographer Benjamin Katz has portrayed protagonists of the art scene from the 1960s to the ’90s. Thirty of these photographs acquired by the Friends since 2014 are portraits of artists whose works are also represented in the Kunstsammlung: Bernd and Hilla Becher, Joseph Beuys, Ulrich Erben, Günther Förg, Katharina Fritsch, Isa Genzken, Katharina Grosse, Georg Herold, Candida Höfer, Jenny Holzer, Donald Judd, Ellsworth Kelly, Per Kirkeby, Konrad Klapheck, Jürgen Klauke, Imi Knoebel, Roy Lichtenstein, Marcel Odenbach, Blinky Palermo, Arnulf Rainer, Gerhard Richter, Thomas Schütte, Richard Serra, Katharina Sieverding, Thomas Struth, Rosemarie Trockel, Günther Uecker, and Andy Warhol. The thirty-first photograph depicts the founding director of the Kunstsammlung, Werner Schmalenbach, in front of a work by Richard Serra, taken during an excursion of the Friends to Houston in March 1990.

-

Höfer, Candida

Schmelahaus Düsseldorf I, 2011With great objectivity and precision, Candida Höfer photographs for the most part deserted interiors of cultural sites such as libraries, museums, palaces, concert halls, theaters, and churches. Here, she provides a view into the large, empty exhibition space of Alfred Schmela’s gallery building, which he opened in Düsseldorf in 1971 and where art history had been written for many years. The image captivates though the clarity of its structure, as well as through an almost classical simplicity and sobriety. With her photographs, the artist presents something that is “actually not modern, something that exudes a sense of longevity” (Candida Höfer, 2001). The artist gifted this C-print to the Friends in 2017.

-

Richter, Gerhard

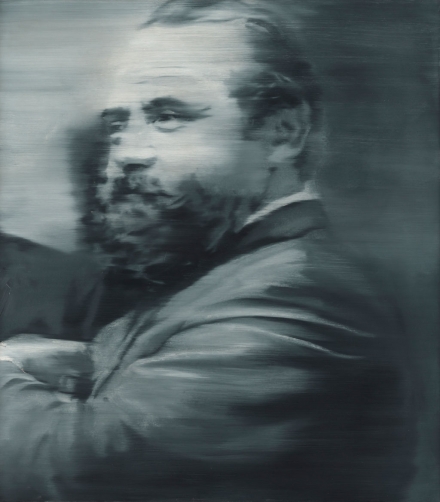

Portrait Schmela III, 1964Gerhard Richter painted Portrait Schmela III after a snapshot taken at the opening of his first solo exhibition at Galerie Schmela. Transferred to the canvas in tones of black, white, and gray and with smeared contours, the portrait appears like a slightly blurred photograph. Its effect is, however, enhanced by the particular harmony of the colors and the chosen detail: The gallerist is presented as an impressive personality, as he was indeed perceived by his contemporaries. The picture was donated by Viktoria von Flemming to the Freunde in 2014. It is the most generous gift the Freunde have received until then.

-

Ad, Reinhardt

Black Painting, 1960–1966Ad Reinhardt’s oeuvre is one of the most radical positions in American painting. Since 1960, the artist has concentrated exclusively on creating the “last painting.” Reinhardt himself described the roughly fifty Last Paintings in the series as the “heroic, black, square ‘breakthrough’ paintings.” They are all square and have a human scale. They have a velvety, almost bodiless surface and initially appear completely black. Only when viewed for a longer period of time do minimal color differences and shapes become discernible. In order to distinguish the different fields, Reinhardt added chromatic colors to the black. Here, the canvas is divided into three vertical blocks of equal size, on which a similar form is horizontally mounted. In this way, a Greek cross with shanks of equal length is created. Nothing refers to a reality outside painting, but everything refers to its constants: color, form, proportions. The painting was acquired by the Friends from a private American collection in 2012.

-

Struth, Thomas

Semi Submersible Rig, DSME Shipyard, Geoje Island, 2007Technological subjects and industrial plants are the motifs of a group of works on which Thomas Struth has been working since 2007. Semi Submersible Rig depicts a drilling platform moored in the port of the South Korean island of Geoje. The strong steel cables that secure the colossus—a sleeping giant—and at the same time draw the viewer’s gaze into the depths of the pictorial space appear at first glance like thin threads. Irrespective of their astute design, Struth’s works always make a contribution to the question of the moral responsibility of the individual in our globalized world. Here, for example, there is a hint of the extent to which our daily lives depend on raw materials that are extracted under extreme conditions for mankind and the environment. Acquired by the Friends in 2011, the work was previously shown in a comprehensive exhibition dedicated to the artist at K20.

-

Platen, Angelika

Joseph Beuys Hamburg, 1968A contemplative, concentrated Joseph Beuys pays tribute to a figure by the sculptor Auguste Rodin. This photo, taken in 1968, is one of the impressive portraits by the photographer Angelika Platen, who has captured many artists on film since the late 1960s. Behind Beuys looms the head and arm of the figure of Pierre de Wiessant, sculpted by Rodin in 1885, one of the courageous citizens of Calais, in whose honor the sculptor created a multi-figure monument. The real encounter in the Hamburger Kunsthalle becomes an imaginary dialog between the elder and the younger.

-

Martin, Kris

1000 Years, 2009The work 1000 years by the young Belgian artist Kris Martin is associated with an unusual announcement: In one thousand years, the massive metal ball will purportedly self-destruct by means of a chemical additive that was added to it during its production. The object will thus lose its status as a work of art. With his work, Kris Martin undermines and questions the classical claim of the artist to create a durable good with a work of art. At the same time, the reference to a period of one thousand years calls for a reflection on temporal categories. The artist thus inevitably confronts the question of what position one takes within the limited, yet seemingly infinite continuum of time. The sculpture was acquired by the Friends in 2010.

-

Sasnal, Wilhelm

Untitled (Hiena), 2008The range of themes and painterly approaches in Wilhelm Sasnal’s oeuvre is remarkably wide. The four paintings acquired for the Kunstsammlung clearly demonstrate the apparent divergence and immediately appealing power of his work. An ostensibly abstract painting such as An Eyelid is, in reality, a radical inner view, attempting to capture the vibrant visions of color behind closed eyes directed at a source of light. In stylistic contrast to this is Untitled (Hiena), a photo-realistically precise modernist interior depicting the body of a dead cat: the attempt to lend a visible form to a family tragedy. A similar contrast unfolds between In the Hood and Kielce. One depicts the view from a closed hood and thus oscillates between the encapsulation of the world of an ego and its encounter with the space outside. The other refers to Sasnal’s recurring preoccupation with what might be called the continuation of the past. It depicts the now demolished ski jump in the city of Kielce, which, with a Jewish ghetto, was part of the National Socialist extermination system during World War II, but also a center of Polish resistance and, in 1946, the site of a pogrom against Holocaust survivors. Sasnal does not approach this abundance of incriminating history directly, but rather through the detour of a landscape that is as melancholic as it is lapidary. The paintings were acquired by the Friends in 2010 from an exhibition of works by the artist in K21.

-

Motherwell, Robert

In Plato’s Cave, 1973In the darkness of the nearly monochrome black-gray, traces of the brush and the varying thickness of the application of the paint—from thin glazing to almost opaque—bear witness to a gestural painting process. The square, outlined with a precise line, stands in stark contrast to this, like a window in a dark, cave-like pictorial space. In the Open series from 1967, to which In Plato's Cave belongs, Motherwell reflected on the significance of the motif of the window in the history of painting. The title also refers to Plato’s allegory of the cave. Here, the Greek philosopher describes the scenario of people who, chained in a cave, can see nothing but the shadows of the things that happen behind them. They perceive this as the only reality known to them. The acquisition of this work by the Friends in 2010 was made possible by a considerable contribution from a private collector from Cologne.

-

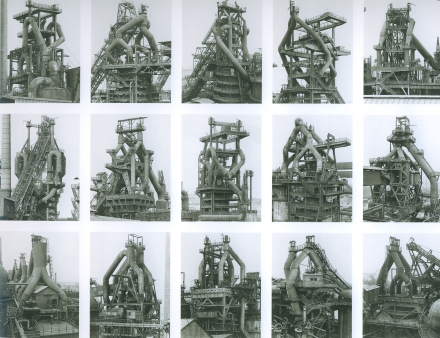

Becher, Bernd and Hilla

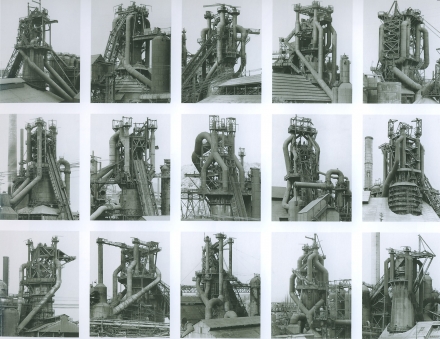

Blast furnace heads, high perspective, USA, 1978–1986Blast furnaces, the heart of every steel mill, play a special role in the photographs of industrial structures shot by the artist couple Bernd and Hilla Becher. Without a protective covering, a branching of pipes and lines emerges, which makes the functionality of the constructions seem more enigmatic than understandable. With the help of a standardized photographic procedure and a particular viewpoint, the artists isolate the objects from their confusing surroundings and thus make them readable and comparable. Compiled in so-called “typologies,” not only the functional commonalities of these industrial giants can be grasped, but also formal differences and structural or country-specific features. The Freunde acquired the typology of the blast furnace heads shot in Germany and Belgium, while those from the steel regions of North America were gifted by the artists to the Freunde.

-

Beuys, Joseph

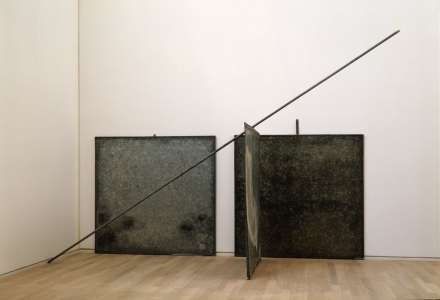

fat up to this level I, 1972With fat up to this level I, Joseph Beuys poses questions about the use of energy with almost minimalist clarity. A continuous horizontal line drawn on the surface of the zinc plates in pencil indicates the potential fill level of the fat, which is invisibly trapped as energy between the plates. Due to its easily changing aggregate states, this substance is particularly suitable for visualizing an energy potential. The fragile placement of the iron rod suggests a sense of floating lightness, which stands in stark contrast to the physical heaviness of the material. The object was acquired for the Kunstsammlung by the Friends in 2003.

-

Ernst, Max

La carmagnole de l’amour, 1926In the late 1920s, the motif of embracing bodies and their balancing act between brutality and passion, movement and inertia, emergence and disappearance, enriched the pictorial world of the Rhenish painter Max Ernst, who lived in France at the time. The woman’s transparent body, drawn with a few brushstrokes, begins to dissolve in the man’s upper torso, which is surrounded by a supporting structure. The indefinite pictorial space, the unstable position of the couple, the evenly applied gray of the pictorial ground, and the light drawing of the woman’s body leave the picture in a state of suspension: between intimation and completion, drawing and painting, black-and-white and color, figure and ground.

The painting was acquired by the Friends in 1999 from the heirs of a paint merchant and plumber from Brussels who had installed a bathroom for René Magritte in the late 1930s and had been “remunerated” with this painting by Max Ernst. A handwritten note confirms this deal.

-

Kelly, Ellsworth

Green Relief with Blue, 1993Kelly’s works from the early 1990s are both paintings and reliefs. Green Relief with Blue consists of two panels that are not placed flush next to each other, but rather one on top of the other. Both rectangular panels have the same height but differ in width. The larger green panel tilts obliquely; the lower right corner is anchored to the lower right corner of the blue panel, while the upper right corner points to its left edge. The interaction of the two panels gives the impression of floating; gravity appears to have been suspended. The pictorial object was acquired for the Kunstsammlung by the Friends in 1997.

-

Twombly, Cy

Untitled (Rome), 1979–2011The relatively rare sculptures in Twombly’s oeuvre are often unstable constructions of found materials, unified by white paint. Only through bronze castings is their permanence ensured. In Bassano in Teverina in the summer of 1979, the artist cast forms for the first time from a mixture of plaster and sand. With two round discs and a triangular disc inserted between them, he invokes the image of an antique chariot and, with the juxtaposition of circles and straight lines, conjures up the elemental power of attack and directionality. The sculpture was acquired by the Friends in 1994.

-

Rauschenberg, Robert

Orrery (Borealis), 1990Rauschenberg worked on the Borealis series from 1988 to 1992. The five brass panels of the present work are covered by a highly heterogeneous cosmos of motifs: The artist screen-printed photographs taken on his travels—a tree trunk, two chairs, a towel, a newspaper, a monkey, and a large clock tower—onto the shimmering surface of the panels in an arch-like arrangement. The only three-dimensional object, a sousaphone, picks up on the materiality of the medium. Rauschenberg reflects on the representability of things and forms of depiction and, at the same time, with Orrery (= a mechanical model of the solar system), presents a projection of the world created by technology. This polyptych was the key work in a comprehensive solo exhibition dedicated to Rauschenberg at the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, at the opening of which the artist himself was present.

-

Ernst, Max

Un chinois égaré (A Lost Chinaman), 1960From time to time (1934/35, 1944, and 1960), the painter Max Ernst devoted himself intensively to sculptural works. He used casts of flowerpots, stones, or tools as building blocks for his figural, often ambiguous plaster objects. Some of the figures were later cast in bronze, others immediately, such as Die Frau von Tours (The Woman from Tours), which Ernst had created as a trophy for the Short Film Festival in Tours. With their matt, delicate surfaces, the white plasters are even more attractive than the bronzes.

Thanks to the mediation of Werner Spies, the Friends were able to acquire the four plaster sculptures from Dallas Ernst, the artist’s daughter-in-law, in 1993.

-

Ernst, Max

La tourangelle (The Woman from Tour), 1960From time to time (1934/35, 1944, and 1960), the painter Max Ernst devoted himself intensively to sculptural works. He used casts of flowerpots, stones, or tools as building blocks for his figural, often ambiguous plaster objects. Some of the figures were later cast in bronze, others immediately, such as Die Frau von Tours (The Woman from Tours), which Ernst had created as a trophy for the Short Film Festival in Tours. With their matt, delicate surfaces, the white plasters are even more attractive than the bronzes.

Thanks to the mediation of Werner Spies, the Friends were able to acquire the four plaster sculptures from Dallas Ernst, the artist’s daughter-in-law, in 1993.

-

Ernst, Max

Un ami empressé, 1944From time to time (1934/35, 1944, and 1960), the painter Max Ernst devoted himself intensively to sculptural works. He used casts of flowerpots, stones, or tools as building blocks for his figural, often ambiguous plaster objects. Some of the figures were later cast in bronze, others immediately, such as Die Frau von Tours (The Woman from Tours), which Ernst had created as a trophy for the Short Film Festival in Tours. With their matt, delicate surfaces, the white plasters are even more attractive than the bronzes.

Thanks to the mediation of Werner Spies, the Friends were able to acquire the four plaster sculptures from Dallas Ernst, the artist’s daughter-in-law, in 1993.

-

Arman

Choral, 1962The Cubists had already destroyed musical instruments—albeit only in the form of a pictorial motif—and with them a piece of the traditional order in which we live. Arman took a more radical path: He shattered or sawed real objects, including string instruments, and arranged the fragments on monochrome pictorial backgrounds. In the early 1960s, he belonged to the Parisian group of Nouveaux Réalistes around Yves Klein and the art critic Pierre Restany, who opposed the predominant abstract art and gestural painting with a new way of dealing with reality. The works were acquired for the Kunstsammlung by the Friends in 1983 and 1990.

-

Baselitz, Georg

Bridge, Tree, Horse, Eagle, House, Jug, Heap, Head 1986By turning the motifs of his paintings upside-down since 1969, Georg Baselitz discovered an innovative way of interweaving formal and thematic contents and demonstrated that pictorial space is always an artificial space with its own laws. Trauriger Gelber (Sad Yellow Man) comes from the time when Baselitz, in addition to his painting, once again turned intensively to sculptural work on figures and heads.

In 1986, Baselitz used various motifs—bridge, tree, horse, eagle, house, jug, heap, head—primarily as the occasion for a painting in which figure and ground become intertwined. In this second work, which also entered the collection thanks to the Friends, isolated, seemingly encapsulated elements are embedded in the white ground in a loose sequence. They appear to circle around the head in the center of the composition, with some overlapping the edge of the canvas.

Both paintings were donated to the museum—mediated by the Friends—by a private patron.

-

Baselitz, Georg

Sad Yellow Man, 1982By turning the motifs of his paintings upside-down since 1969, Georg Baselitz discovered an innovative way of interweaving formal and thematic contents and demonstrated that pictorial space is always an artificial space with its own laws. Trauriger Gelber (Sad Yellow Man) comes from the time when Baselitz, in addition to his painting, once again turned intensively to sculptural work on figures and heads.

In 1986, Baselitz used various motifs—bridge, tree, horse, eagle, house, jug, heap, head—primarily as the occasion for a painting in which figure and ground become intertwined. In this second work, which also entered the collection thanks to the Friends, isolated, seemingly encapsulated elements are embedded in the white ground in a loose sequence. They appear to circle around the head in the center of the composition, with some overlapping the edge of the canvas.

Both paintings were donated to the museum—mediated by the Friends—by a private patron.

-

Nay, Ernst Wilhelm

Schlüsselzeichen (Key Signs), 1962From 1950 onwards, Ernst Wilhelm Nay—one of the most important abstract painters of the postwar period—removed every hint of representationalism in his paintings. From that point on, his aim was to place colors and forms contrapuntally to one other. Beginning in 1955, he composed his pictures from colored discs. Around 1960, the circles became more open, bursting and dissolving at the edges. The painting Schlüsselzeichen (Key Signs) demonstrates how Nay’s painting became increasingly ecstatic and colorful. Rhythms of forms and tones of color combine to form an exciting composition. The painting was acquired for the Kunstsammlung by the Friends in 1986.

-

Modigliani, Amedeo

Portrait of Diego Rivera, 1914The Italian painter Modigliani, who lived in Paris, and the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, who spent time in the French metropolis between 1911 and 1921, were close friends. Modigliani painted several portraits of Rivera, whose voluminous body and round head he depicts here in an open painting style marked by a subtle distribution of dabs of color. This extraordinary portrait entered the collection thanks to a “concerted action” of the North Rhine-Westphalian business community, initiated by the Friends and supported by additional state funds, on the occasion of the opening of the museum’s new building on Grabbeplatz in 1986.

-

Antes, Horst

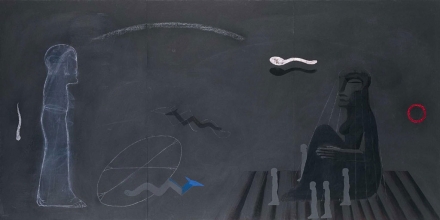

Large Graphit Picture: Seated Female Figure, 1983A remarkable image between archaic myth and modernity. Throughout his life, Antes painted his famous “Kopffüßler” (head-footers), which are curiously reminiscent of pre-Columbian paintings or the small Native American sculptures from Arizona and New Mexico which the artist collected. In this picture, a standing figure faces a seated deity surrounded by other small figures. Symbolic things—a snake, a floating spoon, a falling seed, and two circles—reinforce the mythical dimension of the dark painting, illuminated by only a few color accents, which was donated to the museum—thanks to the mediation of the Friends—by a private patron in 1986.

-

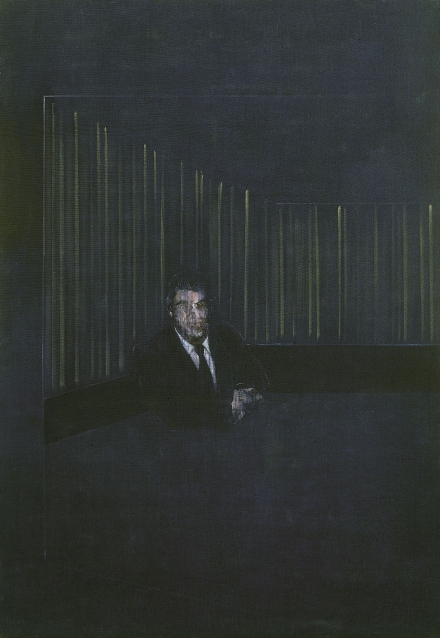

Bacon, Francis

Man in Blue V, 1954In 1954, Francis Bacon painted seven versions of the Man in Blue, seven studies on isolation and loneliness. The work depicts an anonymous figure in a dark, cage-like space defined by merely a few lines. The painter increases the mysterious presence of the man by blurring his physiognomy.

This extraordinary painting would have been out of reach for the Kunstsammlung were it not for the fact that—at the suggestion of the Friends —the Düsseldorf-based bank Trinkaus & Burkhardt, which celebrated a major anniversary in 1986, documented its traditional connection to the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen with an extremely generous donation on a scale without precedence in the history of the museum. The painting was ceremoniously presented to the Kunstsammlung on the occasion of the opening of the new building on Grabbeplatz in 1986. Since then, the lecture hall has been known as the Trinkaus Auditorium.

-

Uecker, Günther

Zwischen Hell und Dunkel (Between Light and Dark), 1983Lightness and darkness, an age-old motif in the visual arts: artists’ perpetual preoccupation with light. It also represents the concept of the duality of all existence that one encounters in nearly every culture. Günther Uecker reduces this to a very simple “formula”: two spirals that rotate around themselves, one dark, the other light. As material, he uses—in addition to a little paint on the unprimed ground—his universal material, the nail, which here describes circling lines, just as, with Fontana, the cut of the knife describes straight lines. Uecker combines the materiality of the nail with the aspired ideality of the image. After 1960, the artists of the ZERO group, to which Uecker once belonged, countered the Nouveau Réalisme of their friends in Paris with a “new idealism.” Uecker’s two-part object was acquired by the Friends in 1984.

-

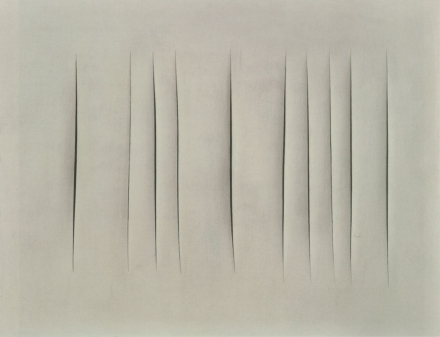

Fontana, Lucio

Concetto spaziale, 65 T 46 (Attese), 1965Although it does not really matter whether lines are drawn with a ruler, a pencil, or a knife: There had to be someone who would use the knife for the first time in a new way, and that someone was Lucio Fontana. Among the many artists who used destruction as an artistic means of expression in the twentieth century, it was he who carried out this destruction emotionlessly, with extreme “coldness”: unexpressively, without any affect, as pure pictorial events. With these paintings, Fontana became the “father figure” of that broad movement after the middle of the century that ranged from neo-geometry to op art—and thus not least of all to the ZERO group in Düsseldorf. The Friends acquired this painting with ten cuts for the Kunstsammlung in 1984.

-

Arman

Colère de Violon, 1963The Cubists had already destroyed musical instruments—albeit only in the form of a pictorial motif—and with them a piece of the traditional order in which we live. Arman took a more radical path: He shattered or sawed real objects, including string instruments, and arranged the fragments on monochrome pictorial backgrounds. In the early 1960s, he belonged to the Parisian group of Nouveaux Réalistes around Yves Klein and the art critic Pierre Restany, who opposed the predominant abstract art and gestural painting with a new way of dealing with reality. The works were acquired for the Kunstsammlung by the Friends in 1983 and 1990.

-

Klapheck, Konrad

Vergessene Helden (Forgotten Heroes), 1965The visual power of this small painting is extraordinary: The seemingly endless row of niches, set diagonally to the picture plane and partially cut off, is reminiscent of the wall of a columbarium. Are the titular “Forgotten Heroes” laid to rest here? The hybrid forms—busts or urns—placed in the niches, as well as the small shimmering forms with their soft outlines presented on some of these, underscore this impression. With sharp precision and intense colorfulness, Konrad Klapheck creates real scenarios, often with a touch of the oppressive or the fantastic.

-

Francis, Sam

St.-Honoré, 1952Sam Francis studied in San Francisco, where he created his first abstract painting in 1946. His painting style was soon unmistakable: Biomorphic, mollusk-like forms filled his canvases. In 1950, Francis left his native California and moved to Paris, where he became an important mediator between the gestural art of the French Tachists and the American Abstract Expressionists. St. Honoré is one of the last pictures in his series of White Paintings. Both the restrained coloration and the title refer to the time in Paris before Francis turned to intense red, blue, and black tones after various sojourns in the south of France.

-

Nicholson, Ben

Dec 1965 Amboise, 1965Ben Nicholson’s painterly oeuvre oscillates between pure abstraction and the representational, albeit reduced language of his still lifes and landscapes. He used the architectural constructions of his paintings and reliefs composed of rectangles and circles to express a—also “musical”—relationship between form, color, and sound. The painted relief created in December 1965 alludes to the small town of Amboise on the Loire, where Nicholson had worked the previous summer.

-

Torfs, Ana

Anatomy, 2006Representing and presenting, reality and fiction form the cornerstones of the slide and video installations with which the Belgian artist Ana Torfs retells and visualizes literary, historical, and political topics. In Anatomy, she addresses the trial following the murder of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht. Ana Torfs selected concise, contradictory statements from the extensive files and had them spoken by actors. On various levels, she combines text and images taken at the anatomical theater of the Charité hospital in Berlin into an installation in which all eyes are directed to the center of the room, to the dissection table. The object to be dissected is, however, invisible and only comes to life in the viewer’s imagination.

Further acquisitions are realised by the the “Stiftung Junge Kunst” (Young Art Foundation), managed by the Friends of the Kunstsammlung NRW

-

Cramer, Catherina

A Boxed RebellionDuring a trip through United States, Catherina Cramer (b. 1988) discovered one of the storage facilities that have been installed in the suburbs of large cities since the 1960s to store a wide variety of objects. Contrary to their original purpose, these rentable units are increasingly used as living and working spaces. In her video, the artist depicts the lives of fictional communities inhabiting such a facility, people who seal themselves off from the contaminated outside world in claustrophobic spaces and test alternative models of living together. She examines the status of the body in an everyday life dominated by new technologies and digital media and presents the video in an accessible container made of corrugated iron.

A Boxed Rebellion was created in 2019 as a final project at the Düsseldorf Academy of Art and was selected and acquired by the Stiftung Junge Kunst in the spring of 2020 from the graduate exhibition Coming to Voice at K21.

-

Mikołaj Sobczak, Nicholas Grafia

X-Filed (Freak of the Week I & II), THE ACCURSED ONESMikołaj Sobczak (b. 1989) and Nicholas Grafia (b. 1990), an artist duo since 2014, address a wide range of the topics: identity, racism, queerness, the historical politics of Poland under the rule of the PiS (Law and Justice) party, and the colonial history of the Philippines

The title of the diptych X-Filed (Freak of the Week I & II) alludes to the U.S. television series The X-Files, which enjoyed great popularity in the 1990s. The protagonists, FBI agents Dana Scully and Fox Mulder (I) tried to solve criminal cases that defied all rationality. The term “freak” also refers to the rhetoric of LGBTQ opponents. Next to them (II), Nicholas Grafia portrays himself in costume from the performance THE ACCURSED ONES, which he realized together with Mikolaj Sobczak in Warsaw in 2018. Attached to the whip in his hand is an identity card—the document that confirms and protects affiliation but can equally serve to exclude. The canvases and the video combine to create an installation of subversive power.

-

Shawky, Wael

Cabaret Crusades: The Secrets of Karbalaa, 2015The correlations between religion and politics, as well as the social reception of events, are themes that the Egyptian artist Wael Shawky explores in his videos and installations. Between 2010 and 2014, he dedicated the three Cabaret Crusades films (The Horror Show File, The Path to Cairo, and The Secrets of Karbala) to the history of the Crusades, a theme that is still highly topical today, more than a thousand years later, due to the ongoing conflicts and wars over the city of Jerusalem. Based on the Battle of Karbala (680 C.E.), Shawky tells the story from an Arab point of view: From this other perspective, the story of the “liberation” of Jerusalem, which is familiar in the West, becomes a chronicle of mass murder, looting, and the lust for power. Glass marionettes on strings act literally as though by remote control, embodying questions about the possibility of political action, power, and manipulation.

The Stiftung Junge Kunst financially supported the shooting of the films in K20 and received one edition of the film in return.

-

M'barek, Pauline

Semiophoren, 2013Visible in a dark, undefined space are two hands wearing bright white gloves. Carefully groping and faintly audible, they move about, feeling the edges and contours of blackened objects that only become visible for a brief moment in front of the gloves’ whiteness. Like the space, the objects can be experienced through the interweaving of the senses of sight, touch, and hearing; they become visible and yet remain invisible. The artist borrowed the title, Semiophores, from the museologist Krzysztof Pomian, who uses this term to describe things that only become bearers of meaning beyond their purely material utility in the context of the museum.

-

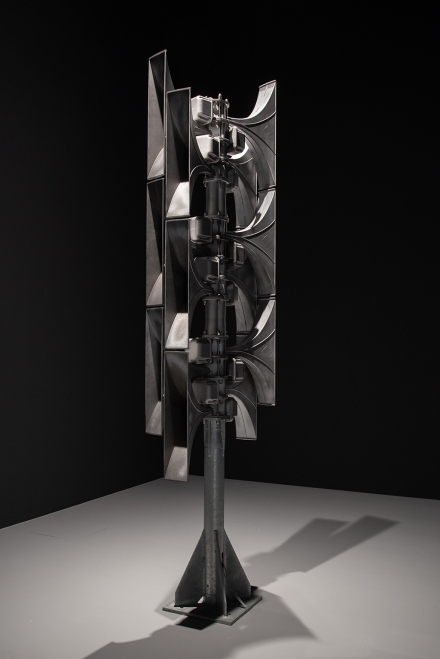

Goethe, Julian

Voices from the Off 1, 2008In 2008, Julian Göthe—an artist, DJ, and long-time set designer for animated and live-action films—developed a group of sculptures for the Nationaltheater and the Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich titled Voices from the Off: larger than life-sized, swelling bodies with round and notably sharp-edged limbs that stand on stable legs. The black-lacquered surfaces, on which the light refracts, shine dimly. They evoke associations with muscular bodies, as well as with designer furniture; they oscillate—according to Göthe—between “a monumentally serious effect and parody” and transform the space into a stage, on which they confront the viewer.

-

Groß, Sabine

Untitled (white cube), 2008Sabine Groß is interested in the parameters within which art is produced and received. She uses various media and materials and prefers digital and mechanical production processes to direct handwriting. The white cube alludes to minimalist objects, which, in the artist’s view, are “suppliers of some of those art formulas”—cube, pedestal, canvas—which are firmly anchored in our concepts of art. The white, reflecting cube marks the beginning of her artistic process, “a mixture of listening [Ger.: Zuhören] and ceasing [Ger.: Aufhören]” (2005), in the course of which an explosion destroys its flawlessness and draws the viewer’s gaze into a dark, fissured interior space.