Shifting Dialogues

Photography from

The Walther Collection

Apr 9, — Sep 25,

2022

Martina Bacigalupo, Sammy Baloji, Oladélé Ajiboyé Bamgboyé, Yto Barrada, Bernd und Hilla Becher, Jodi Bieber, Edson Chagas, Mimi Cherono Ng’ok, Kudzanai Chiurai, Alfred Martin Duggan-Cronin, Theo Eshetu, Em’kal Eyongakpa, Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Samuel Fosso, François-Xavier Gbré, David Goldblatt, Kay Hassan, Délio Jasse, Seydou Keïta, Lebohang Kganye, Sabelo Mlangeni, Santu Mofokeng, S.J. Moodley, Zanele Muholi, Mwangi Hutter, Mame-Diarra Niang, Grace Ndiritu, J.D. 'Okhai Ojeikere, Dawit L. Petros, Jo Ractliffe, August Sander, Berni Searle, Malick Sidibé, Penny Siopis, Mikhael Subotzky, Guy Tillim, Hentie van der Merwe, Nontsikelelo Veleko, Sue Williamson und historisch-ethnografische Fotografien.

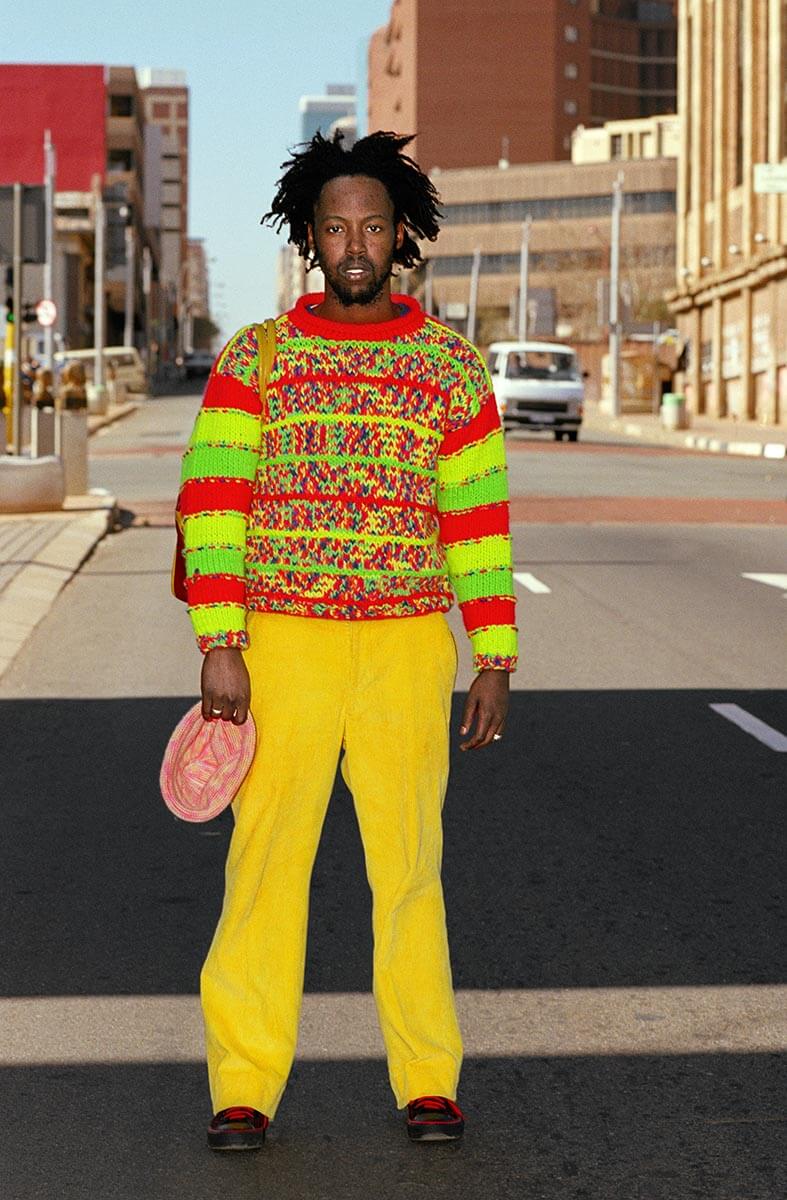

Nontsikelelo (Lolo) Veleko

The K+ Digital Guide for the exhibition “Shifting Dialogues. Photography from The Walther Collection” traces the development of photography as a history of transnational parallels and contradictions. An important point of reference is the 2010 group exhibition “Events of the Self: Portraiture and Social Identity,” curated by Okwui Enwezor (1963–2019) for The Walther Collection.

Susanne Gaensheimer, Director of the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, talks about the exhibition “Shifting Dialogues. Photography from The Walther Collection” at K21

The photographic artworks assembled here systematically reveal the ambivalent – and shifting – relationship between image and self-image, portraiture and social identity, representation, and performance. The K+ Digital Guide showcases the beginnings of ethnographic images during the colonial era, self-determined studio photography—and politics of self-fashioning – from the 1940s onwards, and the potent visual activism practiced by a constituency of contemporary artists in the present.

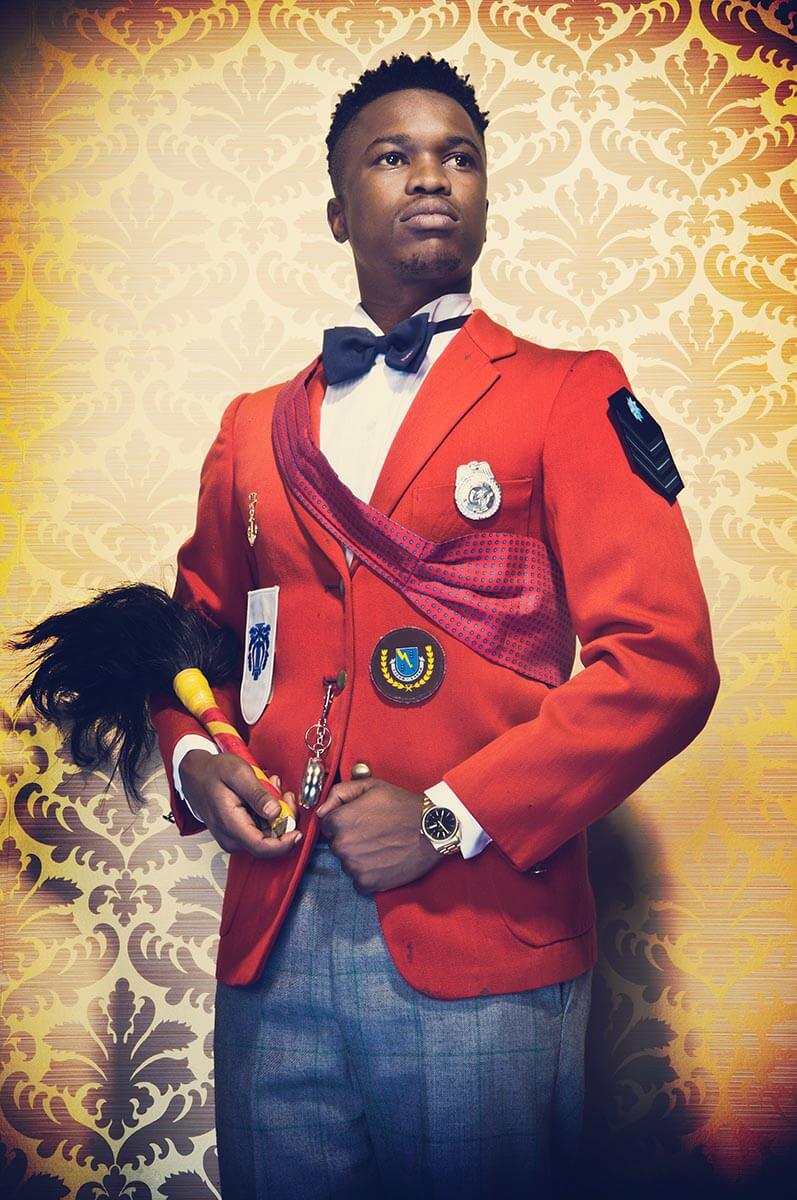

S. J. Moodley

Artist Duo Mwangi Hutter expand the K+ Digital Guide with a newly produced artistic video intervention

The selection brings together a constituency of contemporary artists who use photography to investigate the emancipatory, liberating possibilities of portraiture and self-representation. Photography here becomes a mode to challenge dominant power structures, and a democratic tool to articulate new subjectivities. These thematically diverse, and often serial, bodies of works subversively question binary concepts of gender and cultural identity, oscillating between objective representation, performance, and staged photography.

Moreover, the selected works for the exhibition engage with and critically reflect common Western notions of the African continent.

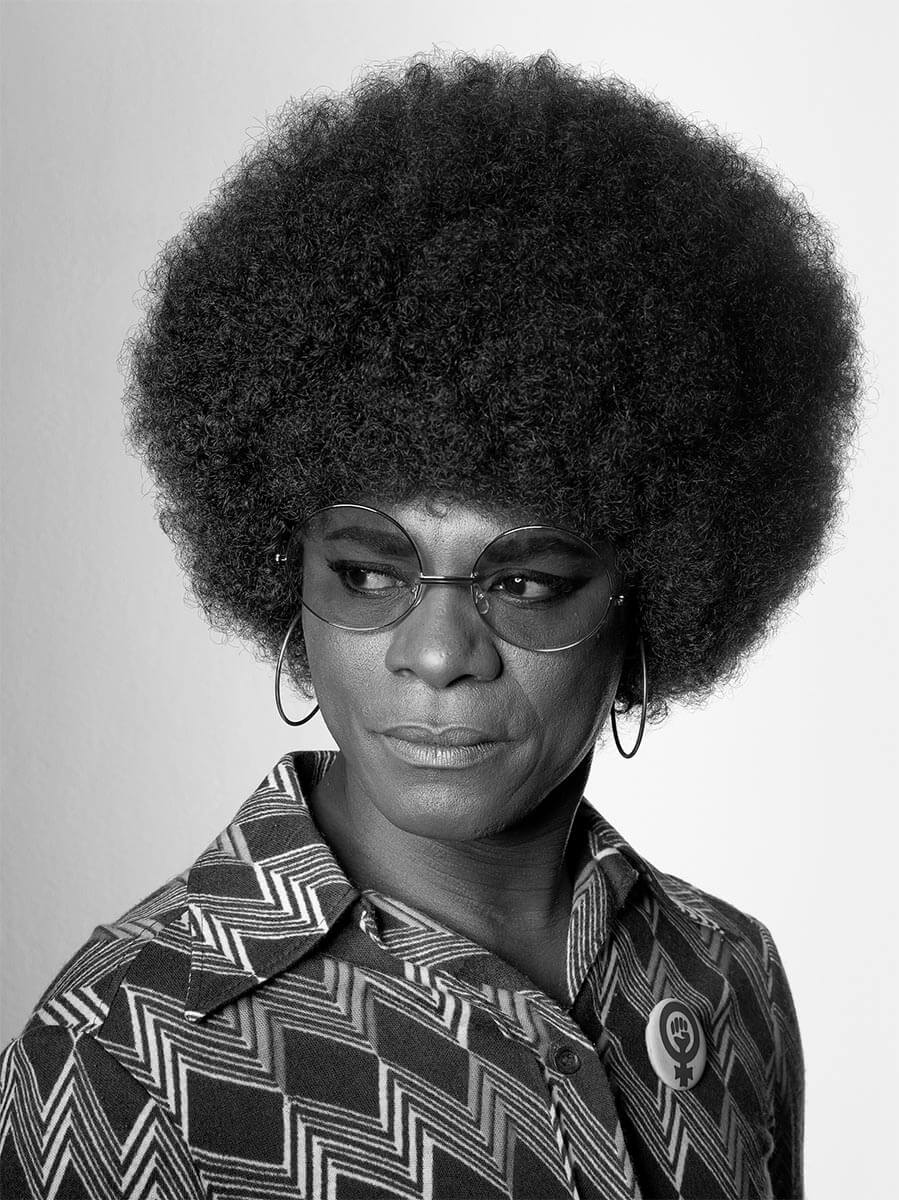

Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi

Since the early 1980s contemporary artists have explored the body as a contested site for the staging – and mapping – of difference: as an expression of economic, cultural, and social inequalities; as a “weapon” against societal constraints and binaries; and as a testament to alternative sexual and gender identities. Photography becomes a performative practice of embodiment, for indigenous and Afro-diasporic visual meditations on integrity, transformation, and representation.

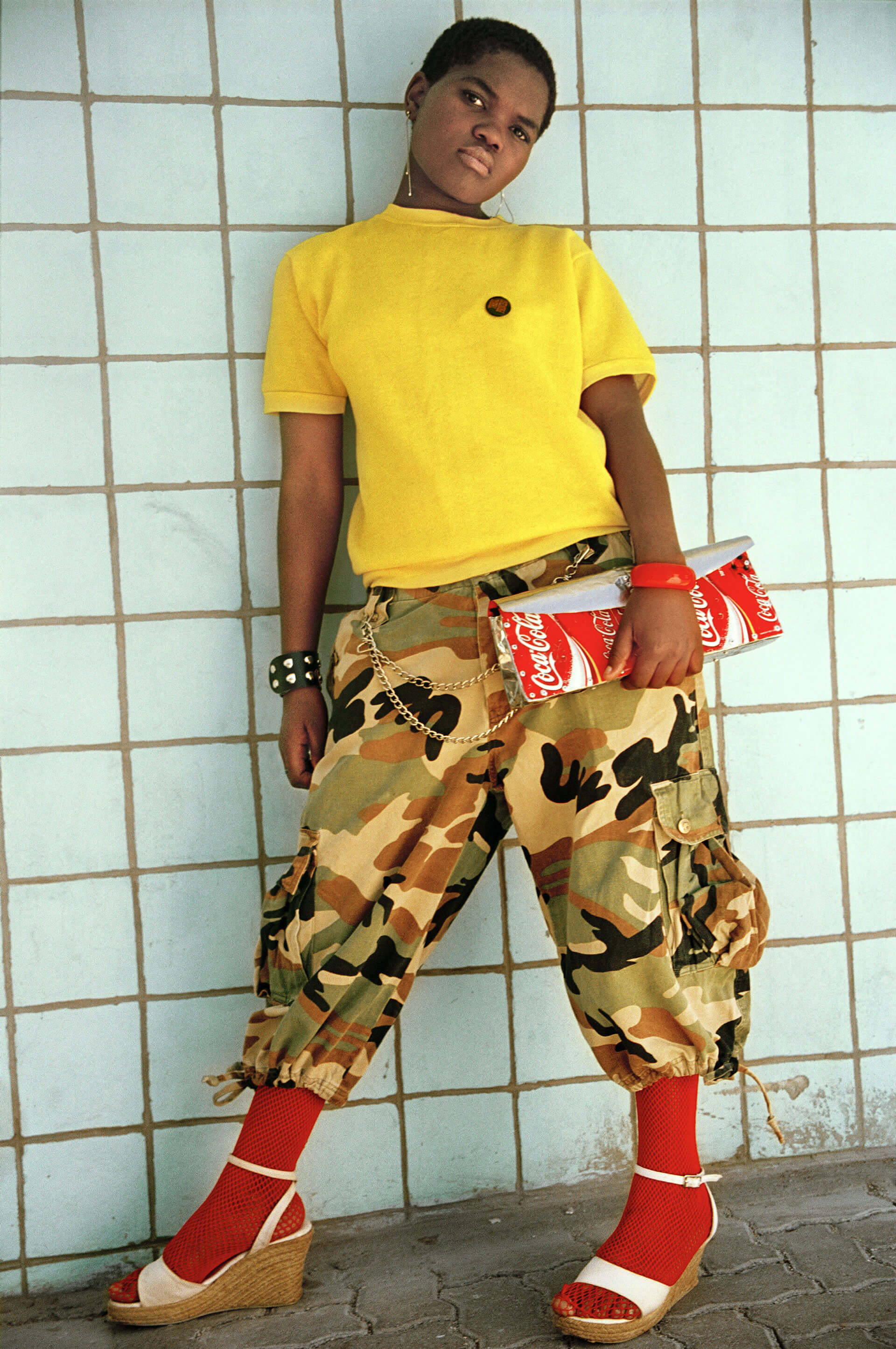

Nontsikelelo Veleko’s protagonists engage in vibrant modes of self-fashioning to express their social, cultural, and metropolitan identities in public spheres. Sabelo Mlangeni’s “Country Girls” (2009) offer an intimate portrait of queer life within rural regions of South Africa, portraying marginalized communities rarely made visible. The very existence and subversive gender queering of drag queen “Miss D’vine” (2007) as portrayed by Zanele Muholi, constitutes a defiant act of resistance, and agential insistence.

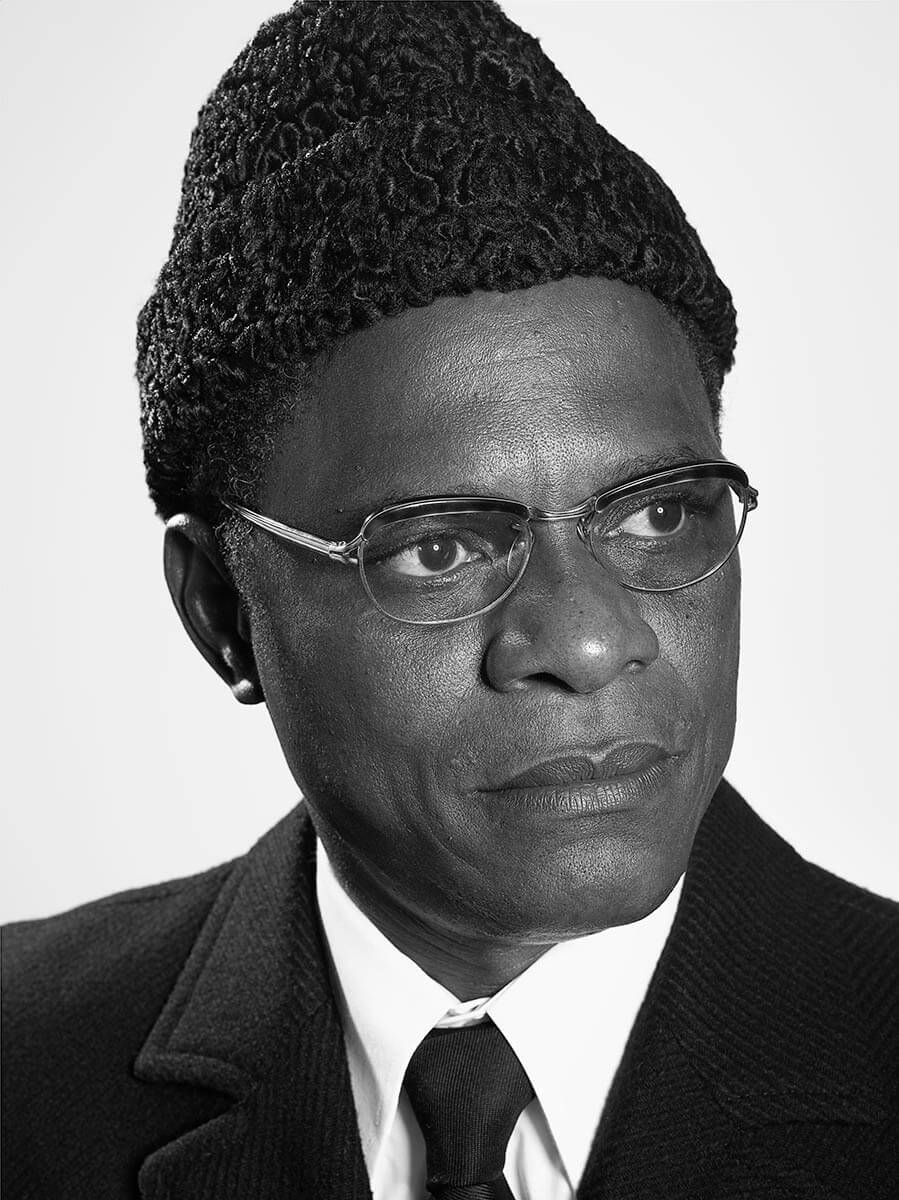

Mwangi Hutter employ their own bodies to express ideas of collective consciousness, and interrogate themes of cultural belonging, heritage, and history, while the carefully constructed iconography of Kudzanai Chiurai’s “The Black President” (2008) questions notions of masculinity and power. Samuel Fosso’s self-portraits in “African Spirits” present the artist posing as icons of the pan-African and civil rights liberation movement. These highly theatrical impersonations not only honor the figures who fought for postcolonial independence and human rights, but also display how their self-styling for the media helped to shape political ideals. S. J. Moodley’s (1922–87) studio portraits from the 1970s show a diverse range of people classified as “African,” “Indian,” or “colored” by the apartheid regime.

Rotimi Fani-Kayode’s imaginative vision of the Black body is infused with spirituality and erotic intimacy, fueled by the artist’s desire to enter a dialogue with his Yoruba ancestors and visualize queer sexuality through the prism of his own identity.

Artist Samuel Fosso talks about his works in the exhibition

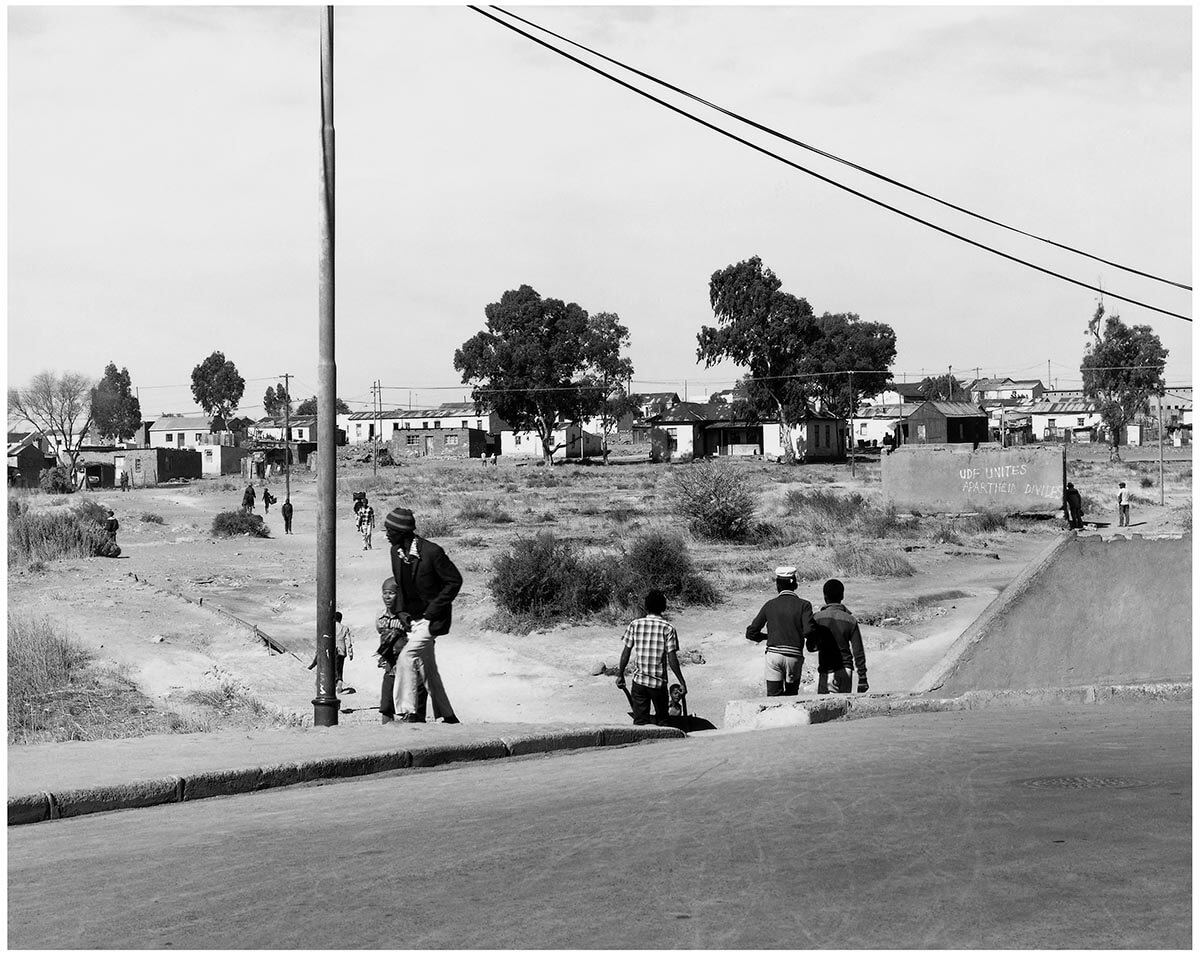

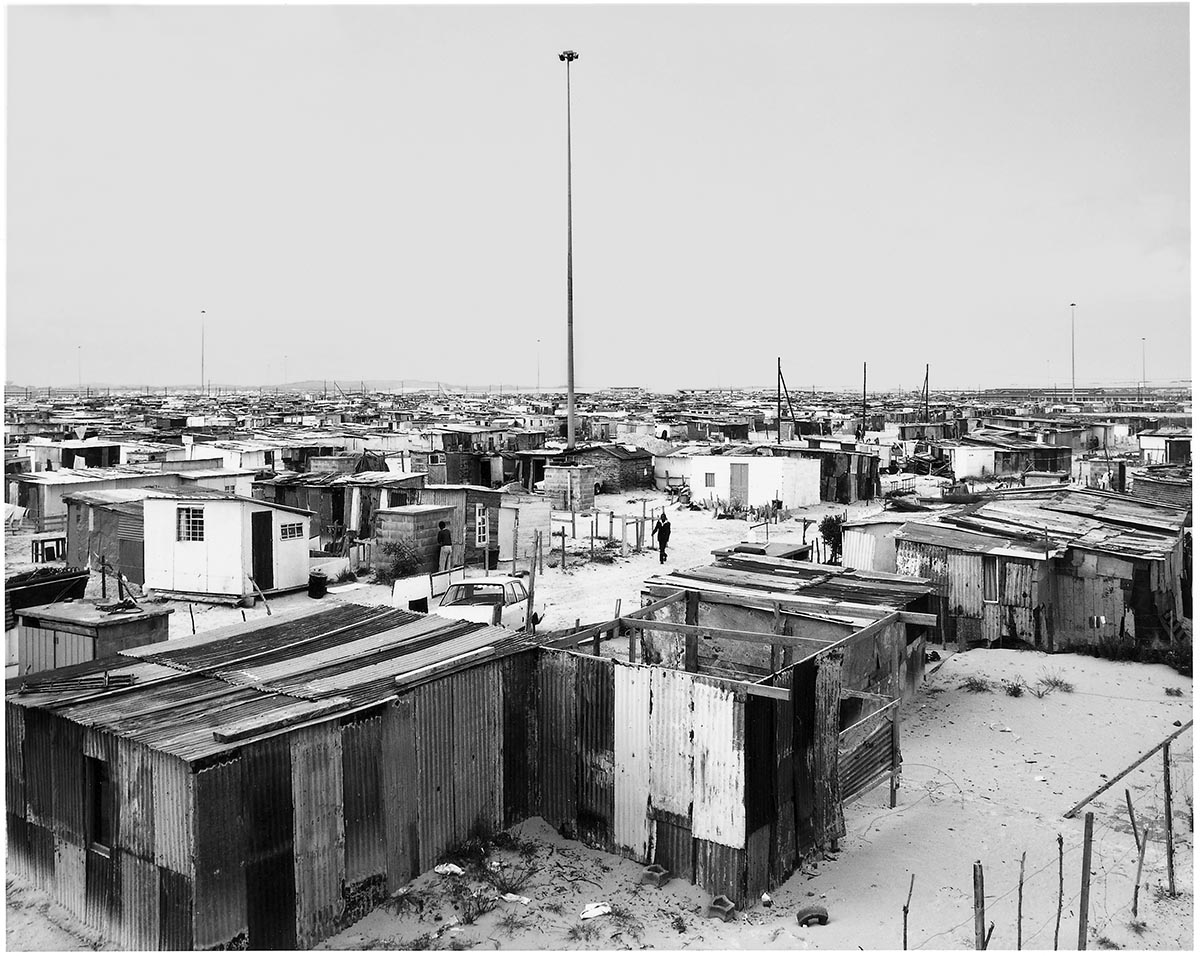

With the city’s dense urban structures and built environment in focus, architecture is pictured here – in the works of Sammy Baloji, David Goldblatt, Jo Ractliffe, Guy Tillim, Em’kal Eyongakpa und Theo Eshetu – as a symbol of social order, of utopian failure, of shattered aspirations of freedom and self-realization. Collectively, the photographs on view represent psychological studies of liminal social spaces, hybrid identities, geopolitical shifts, and (post)colonial conflicts. They show the reverberations of violence – of war, oppression, colonial subjugation – on the contemporary landscapes of South Africa, Angola, Cameroon, and Ethiopia.

Sammy Baloji

The photographs by Ractliffe and Goldblatt act as testaments to memories, reflections of individual and collective histories, and inscribed ideologies. Eshetu’s respective works convey religious, spiritual, and secular sentiments.

The photographs act as testaments to memories, reflections of individual and collective histories, and inscribed ideologies. They show the reverberations of violence – of war, oppression, colonial subjugation – on the contemporary landscapes of South Africa, Angola, and Cameroon.

The works are inscribed with traces of (post)colonial and (post)industrial conflicts as well as testimonies to collective memory and spirituality.

The photographs shown here act as testaments to memories, reflections of individual and collective histories, and inscribed ideologies. They show the reverberations of violence—of war, oppression, colonial subjugation—on the contemporary landscapes of South Africa, Angola, and Cameroon.

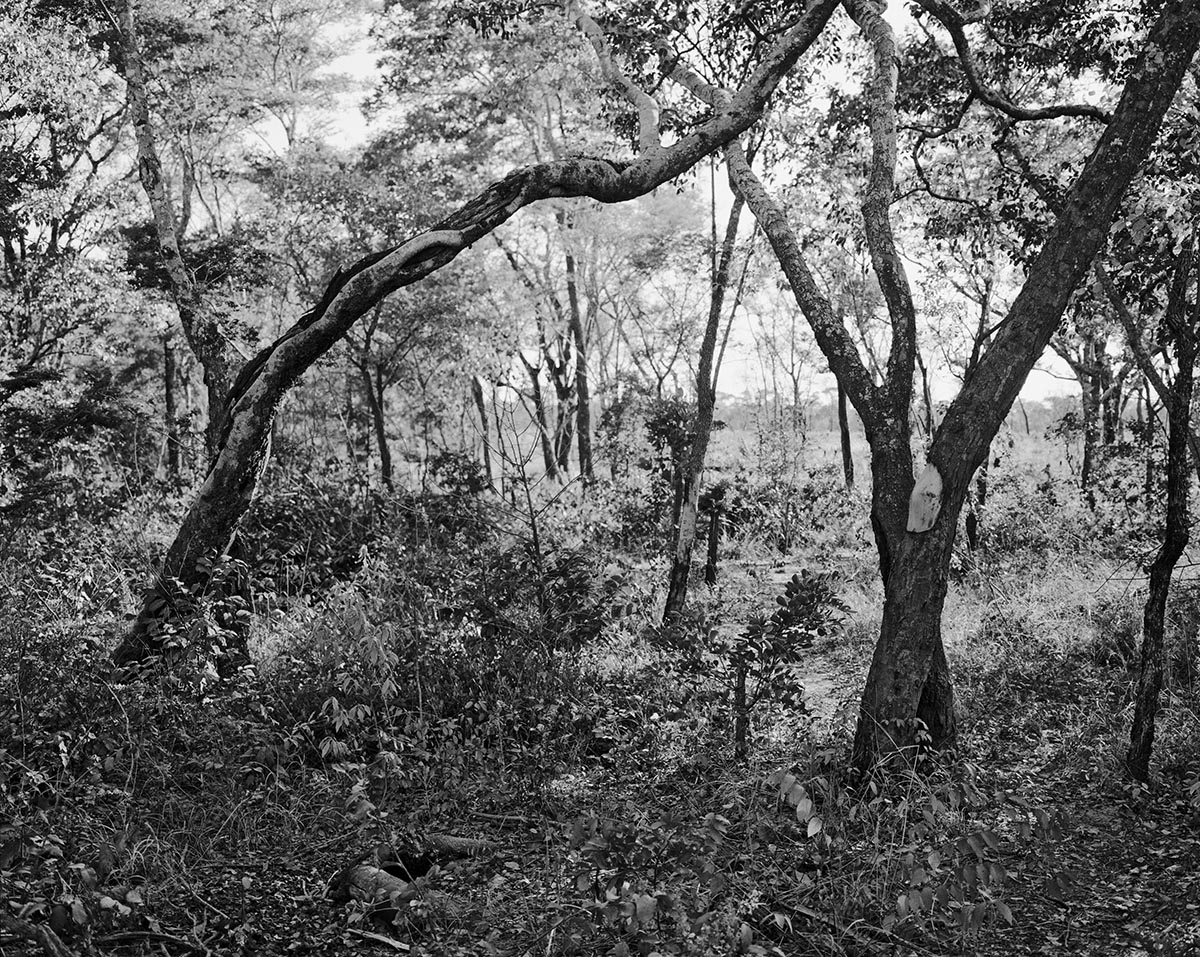

Jo Ractliffe’s “Diana Archive” (1990–94) consists of snapshots taken with a toy camera: photographed between Johannesburg and Cape Town just before the end of apartheid, these ambiguous, fragmentary images are haunted by fleeting traces of people, hovering between visibility and invisibility, absence and presence. With “As Terras do Fim do Mundo” (2009–10) Ractliffe visualized the aftermaths of the Angolan Civil War, exploring “how past traumas manifest in the present landscape, both forensically and symbolically…—in a present space that nevertheless bears the traces of its history.” (Jo Ractliffe)

David Goldblatt too documented the complex conditions and structural binaries in South-African built environments and vast landscapes—shaped by apartheid-era ideologies and racially motivated displacements, forced migrations, and destructions.

The panoramic photomontage works in Sammy Baloji’s “Mémoire” (2006) create a dialogue between archival and contemporary images where figures of the past appear in expansive Congolese post-industrial wastelands to illustrate the parallels between past colonial exploitation and present economic hardship. Guy Tillim’s “Avenue Patrice Lumumba” (2008) documents the monumental architecture that took shape during decolonization in the Democratic Republic of Congo in the 1960s and 1970s as a story of postcolonial dreams. With “Jo’burg” (2003–04), Tillim explores the social and urban changes of a “new South Africa” in his native city.

Em’kal Eyongakpa’s “Ketoya Speaks” addresses Germany’s colonial occupation of Cameroon (1884–1916) through diffused images of fragmentary figures and abstracted forms that recall scenes of violence, yet equally attest to the artist’s belief in the existence of spiritual spheres. Theo Eshetu’s photo-based installation provides a kaleidoscopic insight into the collective spirituality of pilgrims who journey to Mount Zuqualla in Ethiopia, revered by Coptic Christians as a holy site for centuries. This profound cross-cultural significance is reflected in Eshetu’s visual meditations: material and immaterial worlds are united through religious performance, traditional ceremonies, and rituals.

Artist Theo Eshetu talks about his works in the exhibition

Theo Eshetu

The voices of a younger generation of artists are represented with works Délio Jasse, Lebohang Kganye, Mame-Diarra Niang, and Dawit L. Petros.

They contemplate the effects of socio-cultural, economic, and political changes in the present; and creatively explore the influence of capitalist systems on urban environments, collective memory, and politics of migration

Their practice reflects a contemporary paradigm shift in post- and decolonial discourses, offering insights into the present possibilities and complex thematics of contemporary photography from an Afro-diasporic perspective that is at once plurivocal, subjective, and critically engaged.

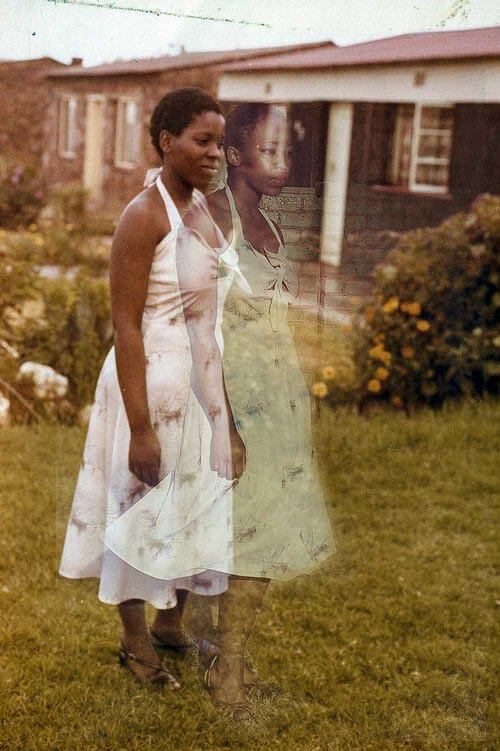

This section is dedicated to the photographs of a younger generation. “Terreno Ocupado” (2014) depicts Délio Jasse’s native city of Luanda in analog cyanotype photographs with overlapping images of people, objects, and streets, visualizing the city in a permanent state of flux.

For her work “Ke Lefa Laka: Her-Story” (2013), Lebohang Kganye superimposes vernacular images from her family albums with self-portraits dressed in her mother’s clothes: the layered collage works show mother and daughter—separated by time and circumstance—united through photography.

Mame-Diarra Niang’s metaphorical works explore the possibilities of photographic representation through decontextualized, abstracted landscapes composed of image fragments that imagine identity as territorial space. Dawit L. Petros’ “The Stranger’s Notebook” (2016) is the outcome of a thirteen-month field trip—from Nigeria to Senegal, Mauritania to Spain, France to Italy—to compare contemporary experience of travel with past narratives of mobility and migration.

Dawit L. Petros

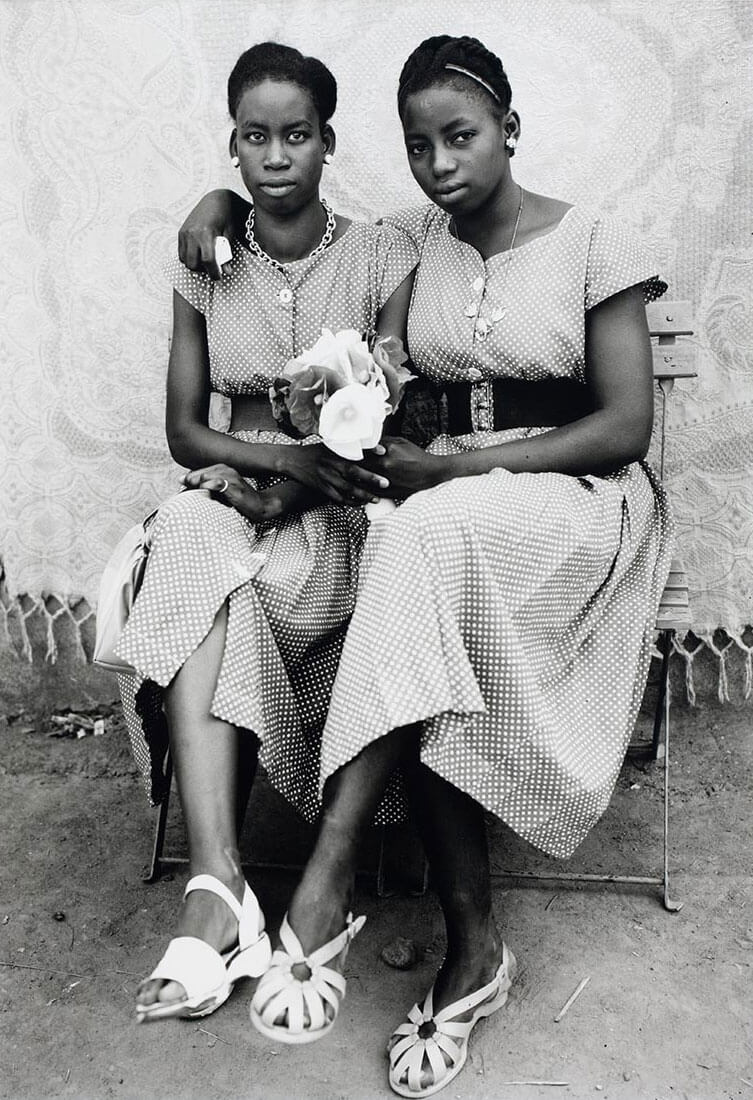

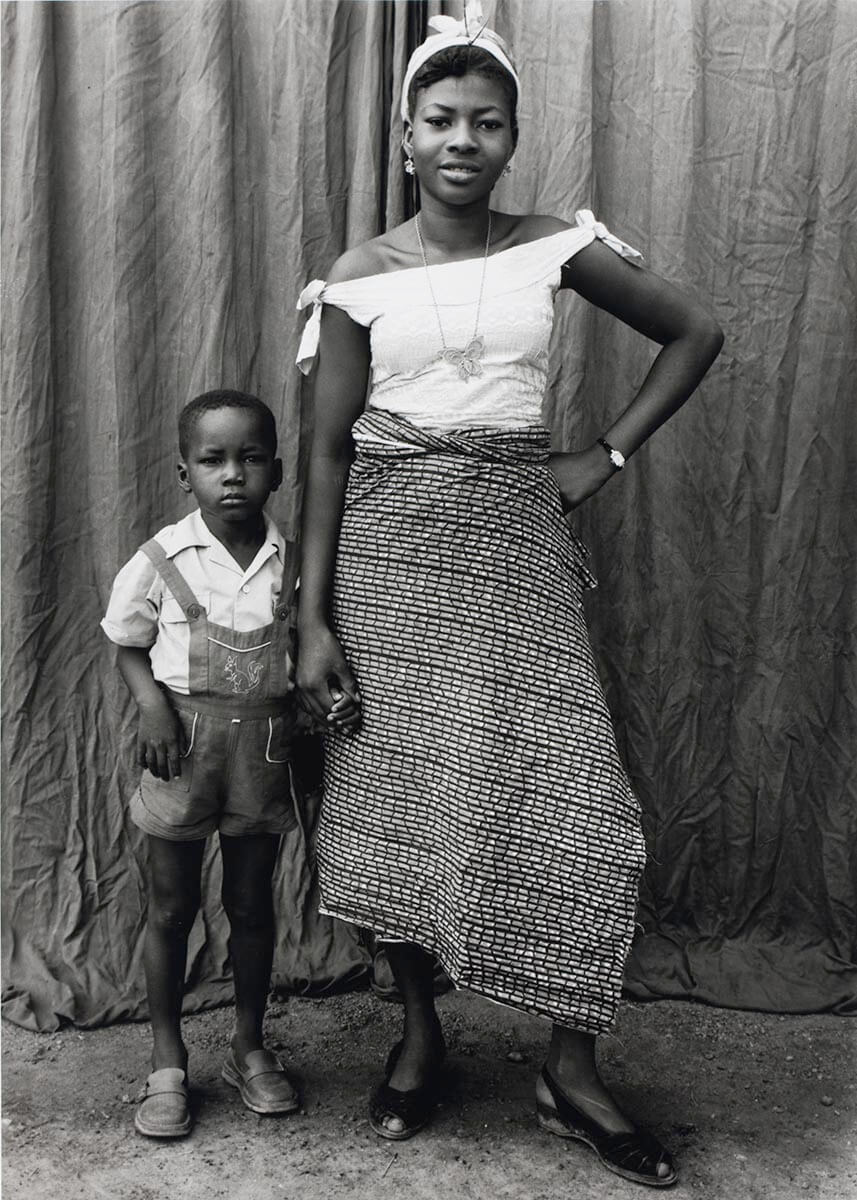

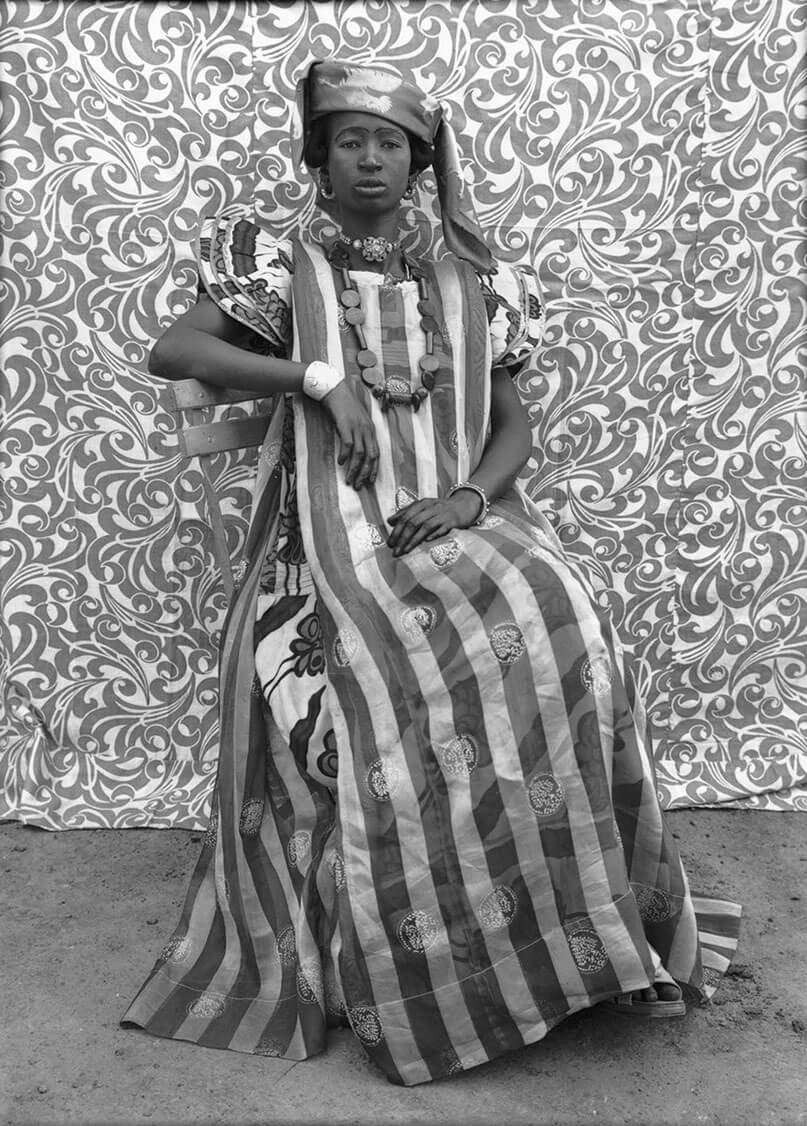

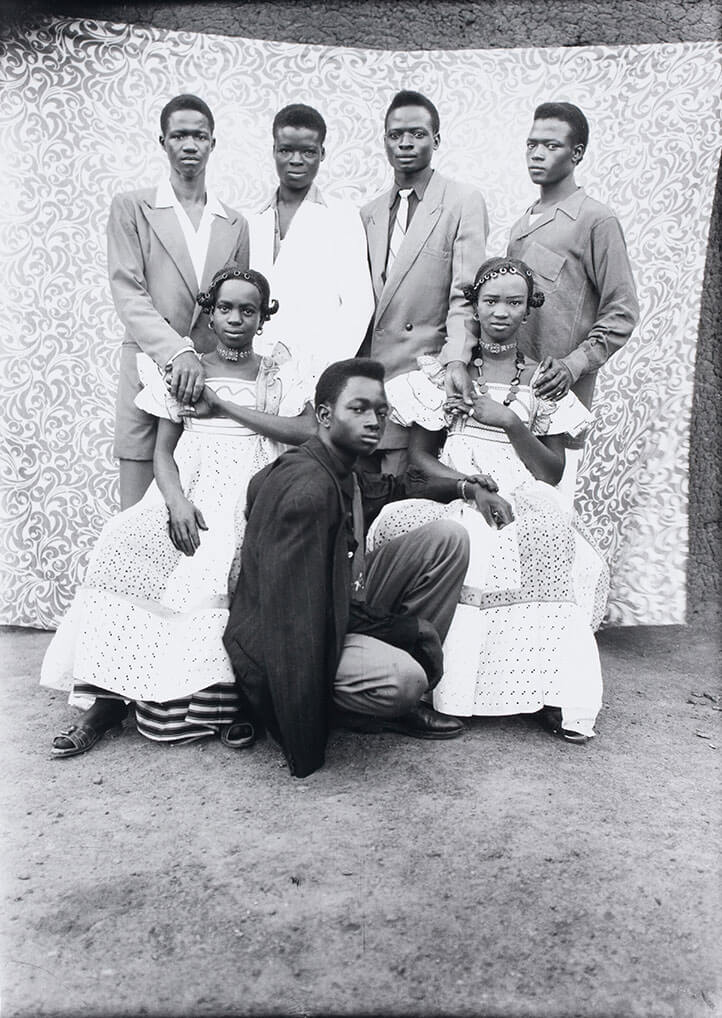

In the dialogue between Seydou Keïta (1923–2001) and August Sander (1876–1964), socio-cultural differences and similarities of two contrasting mid-twentieth century moments become visible: portraying societies in transition, the postures and gestures adopted by the sitters present them as witnesses and active participants in the writing of collective histories and cross-cultural narratives of transformation.

1950s

Seydou Keïta portraits, created in his commercial photography studio in Bamako, depict Malian society during a time of change in the years preceding the country’s independence. His formal portraiture style and skillful compositions shaped the new image of (post)colonial Africa and evidence photography’s growing importance as a modern medium of self-expression. To be photographed by Keïta was to be made “Bamakois:” to be seen as beautiful and cosmopolitan.

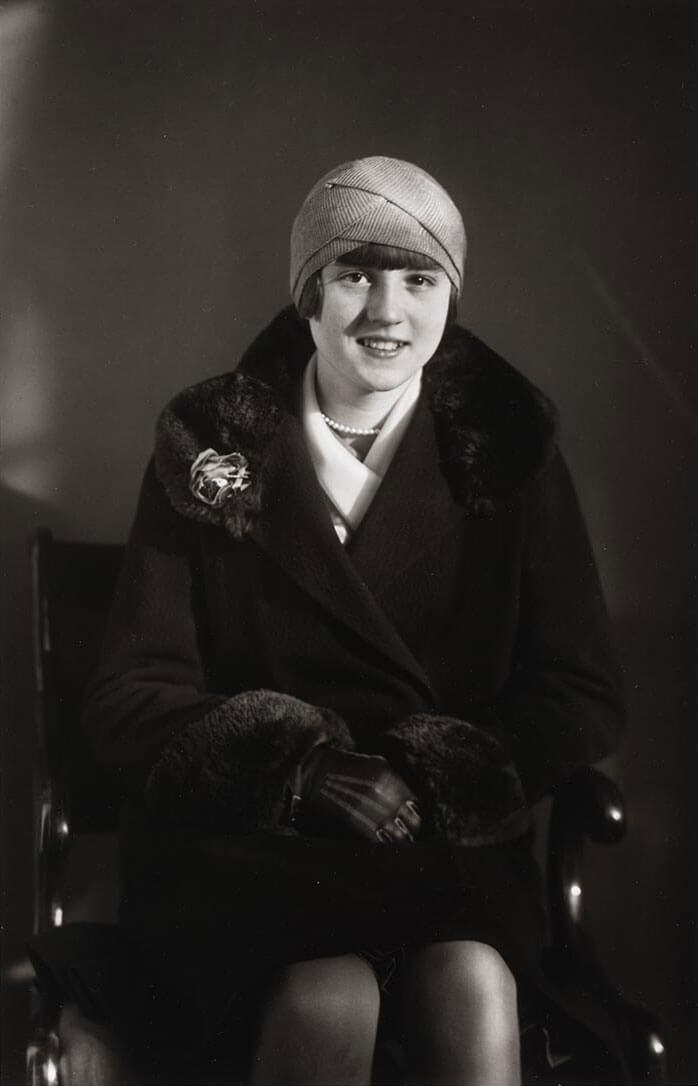

1920s

The photographic image became a tool for self-representation, similar to August Sander’s comprehensive cultural study “Face of Our Time.” Photographed during the Weimar Republic, Sander’s visual portrayals depict a variety of occupational groups, genders, and generations—farmers, workers, students, families, tradespeople, artists, and members of the bourgeoisie—highlighting both the individuality of his sitters, as well as typical traits and markers of class and social status. The structure of Sander’s later major body of work “People of the 20th Century” begins to manifest in this series.

Curator Brian Wallis talks about Vernacular Photography from The Walther Collection

Tamar Garb, Professor of Art History at University College London, talks about selected historical photographs in The Walther Collection

This dialogue between three distinct artistic positions opens up a discursive reflection on conceptual taxonomies, typologies, and seriality—similar to the cross-cultural juxtaposition of works by August Sander and Seydou Keïta.

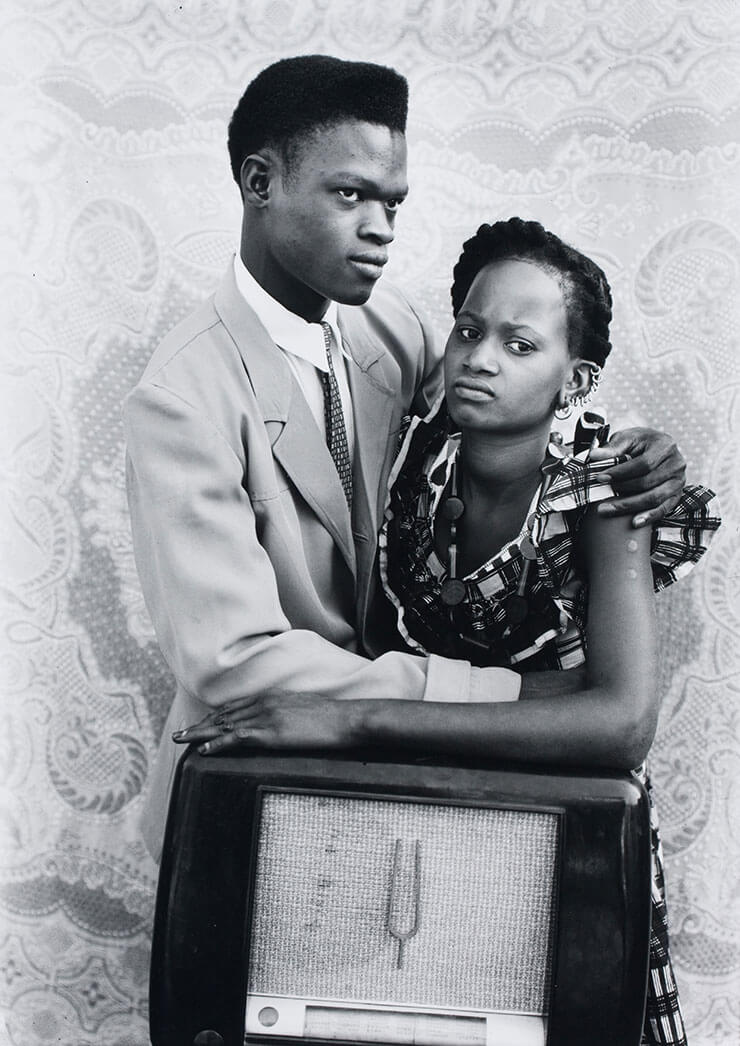

1960s

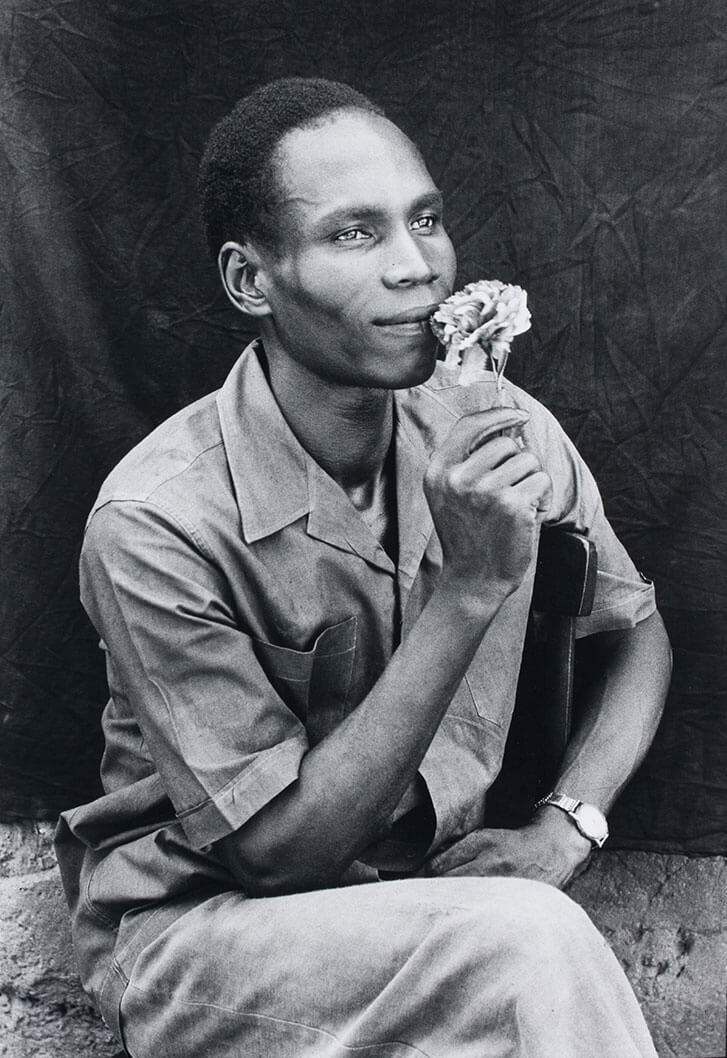

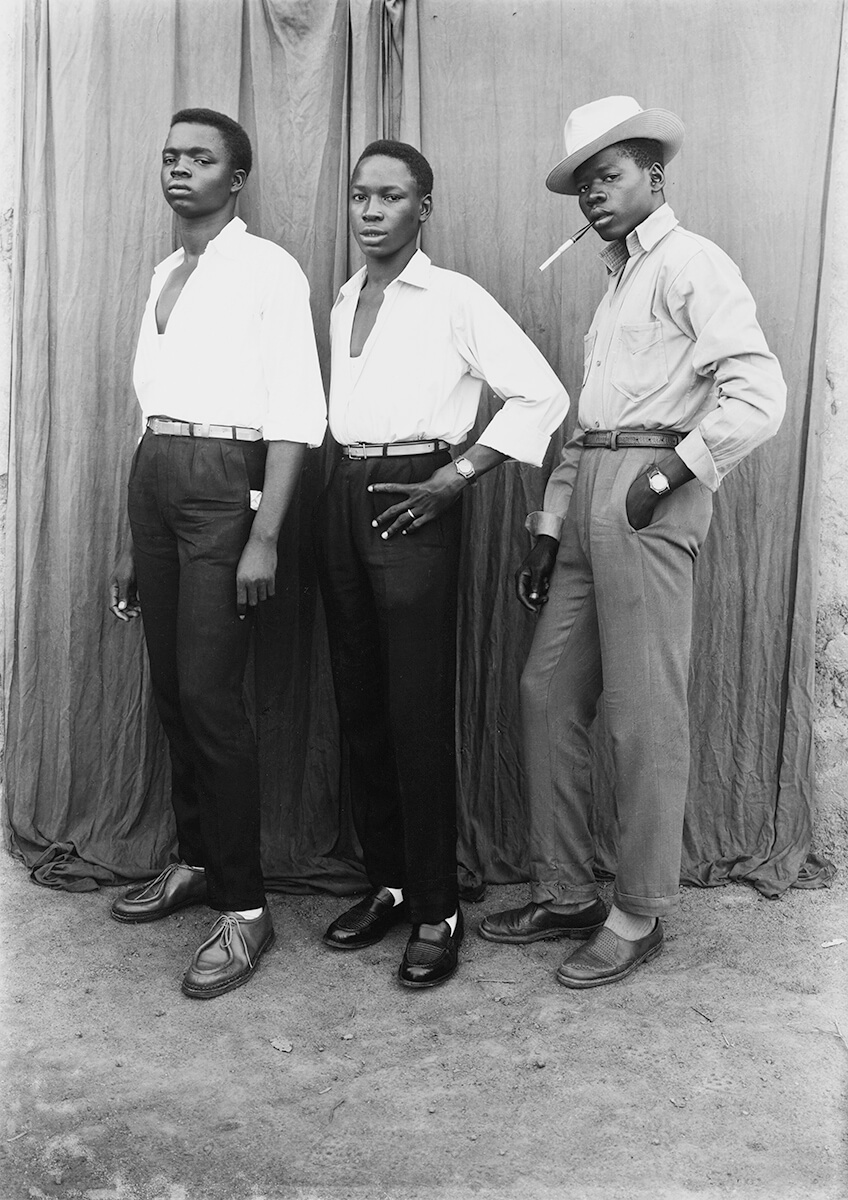

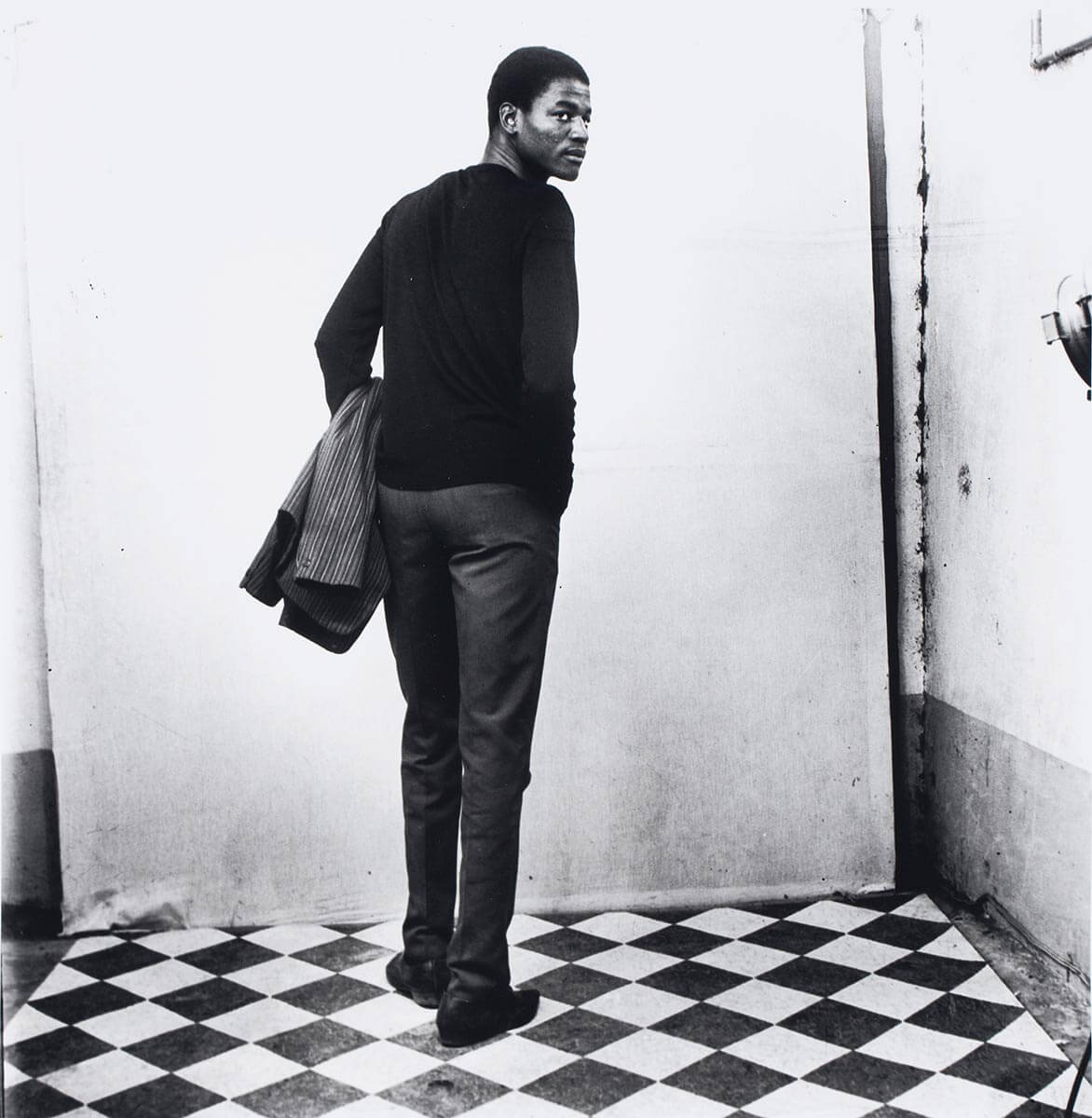

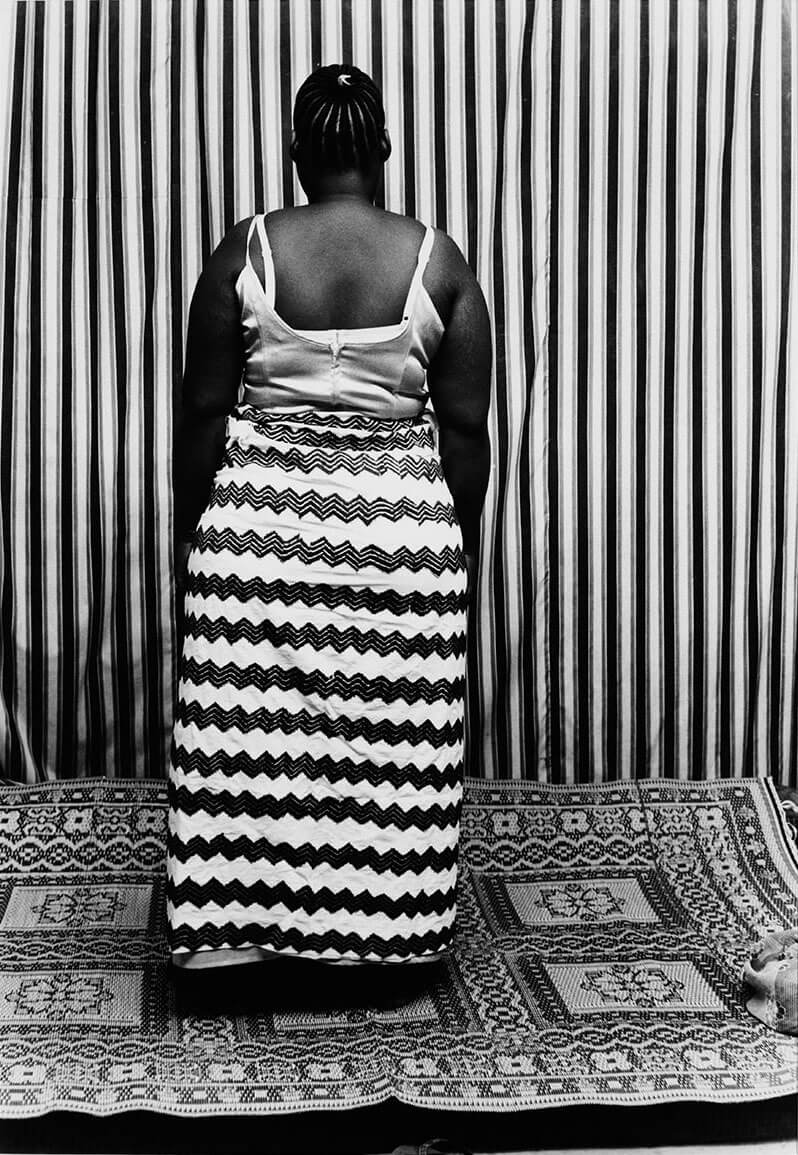

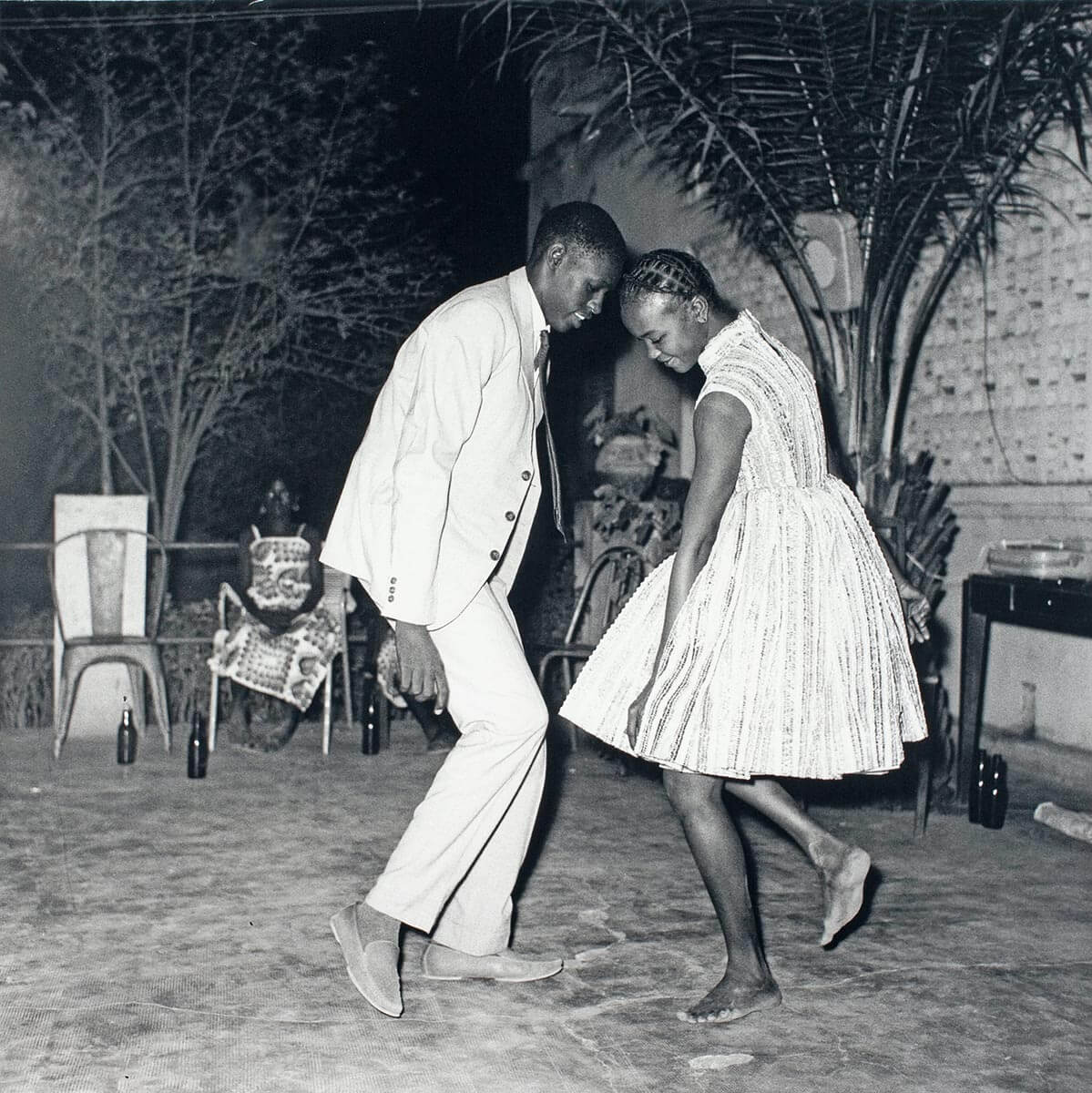

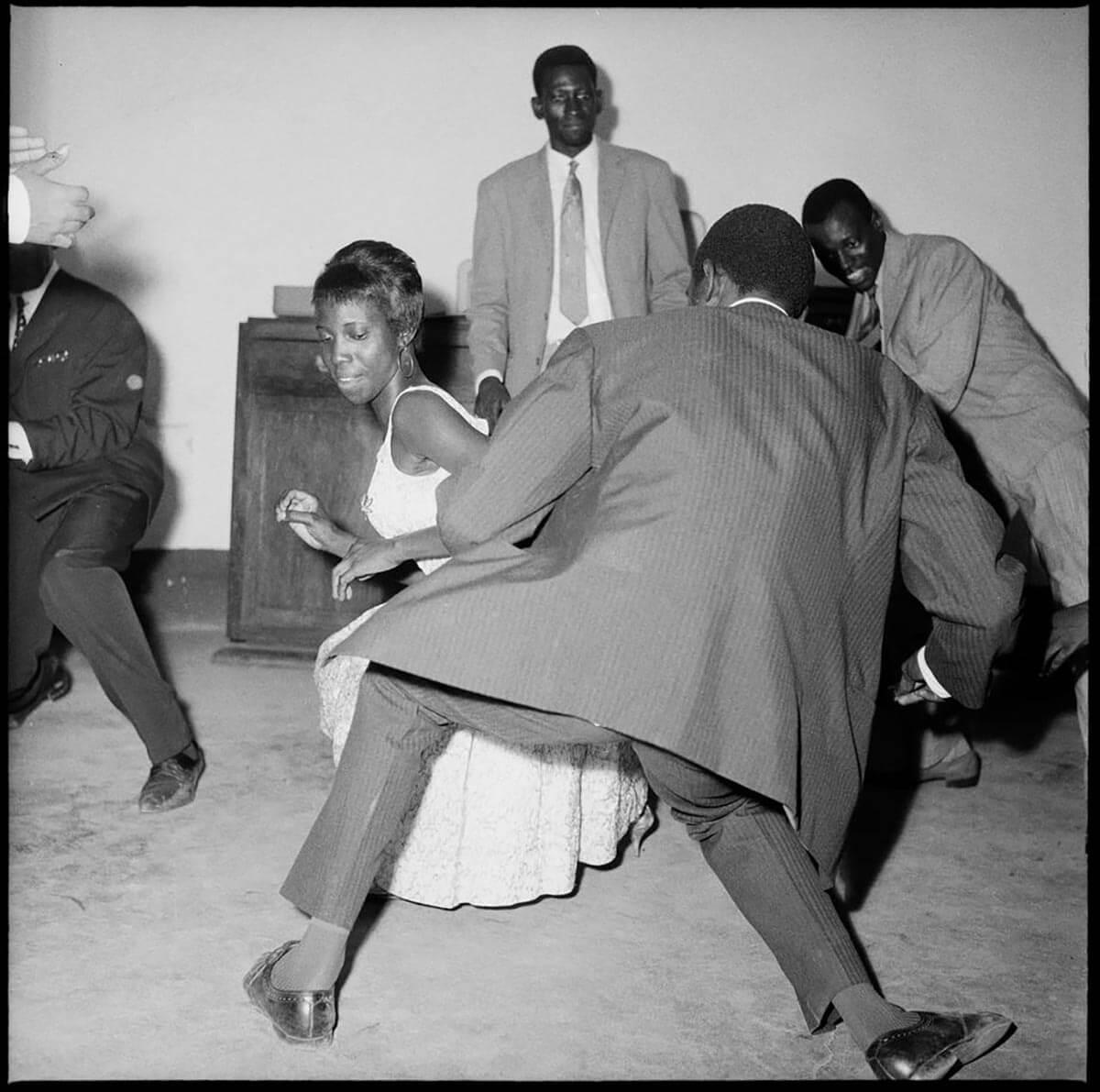

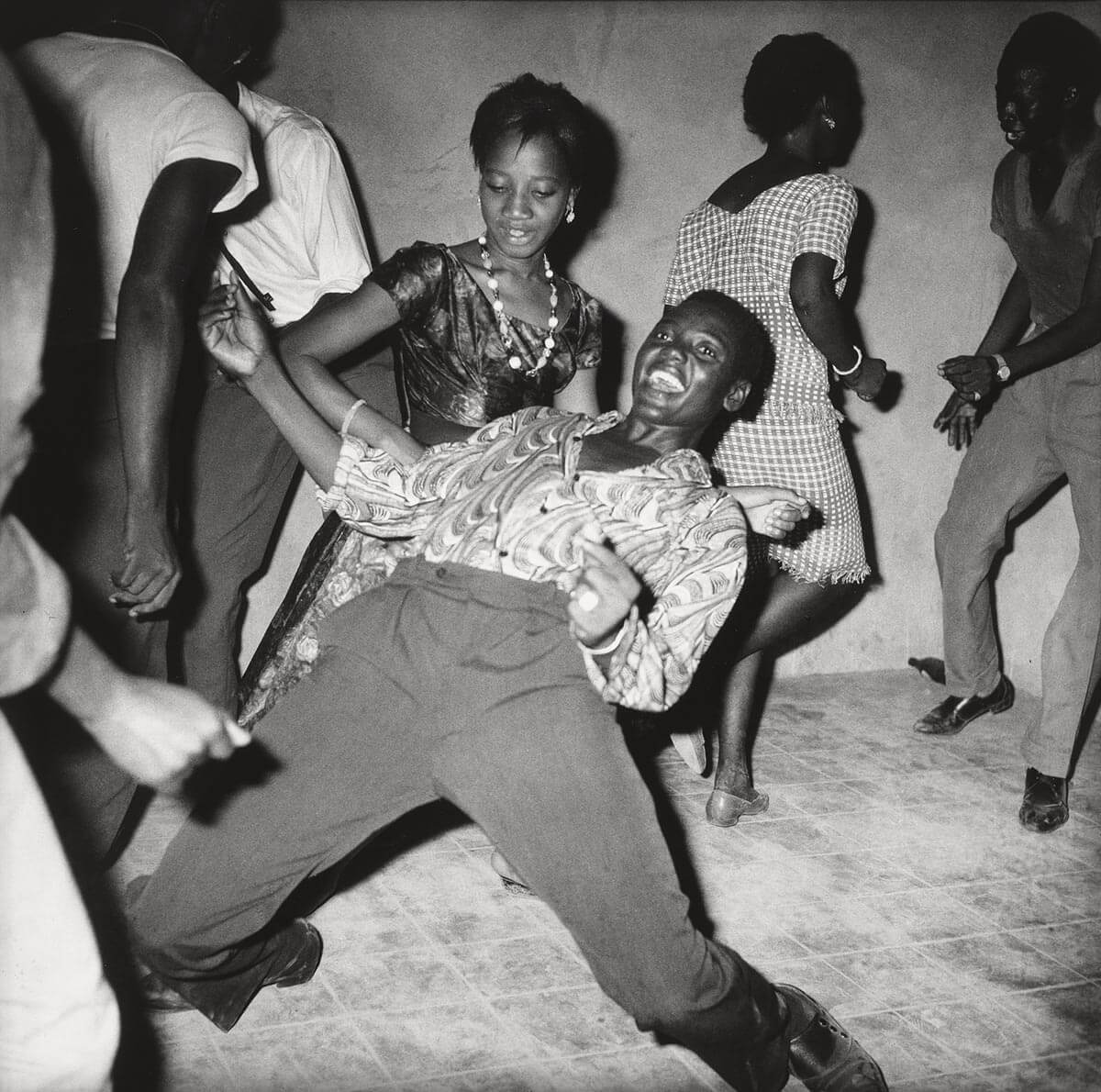

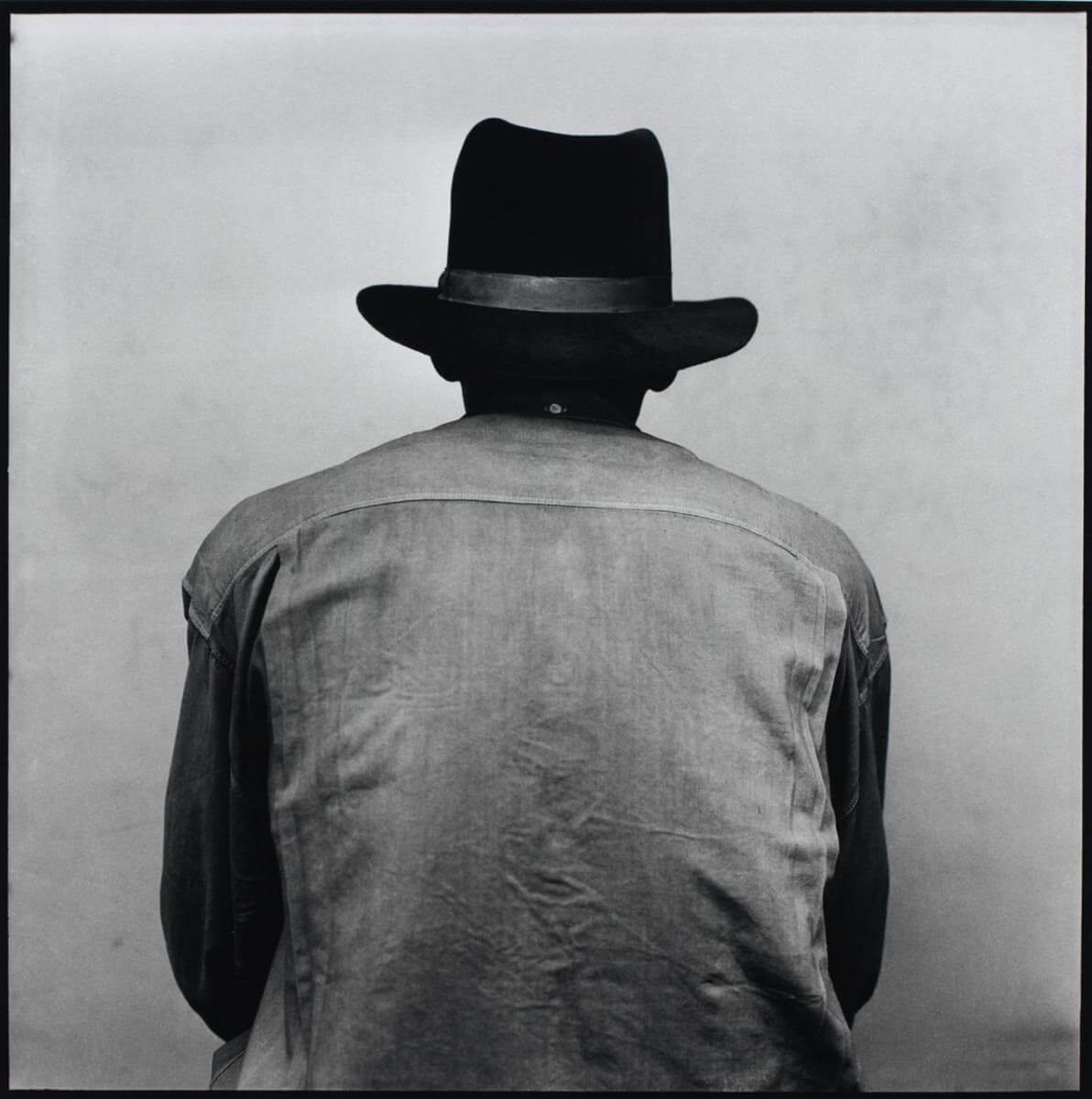

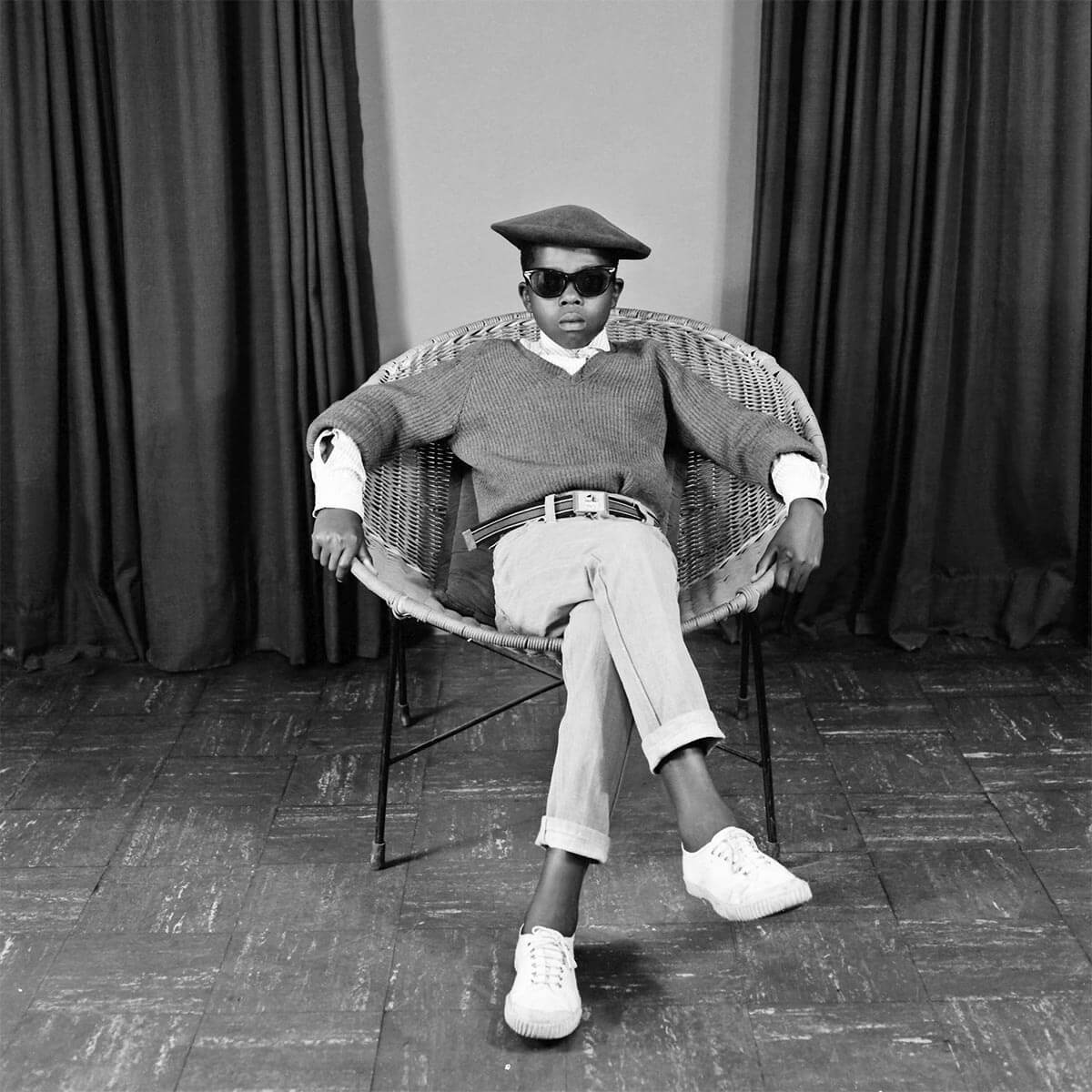

Working in Bamako from the 1960s onward, Malick Sidibé (1935/36–2016) became a chronicler of his time and its people, celebrating a newly emerging identity in postcolonial Mali in the years following its independence: inside nightclubs and on the shores of the Niger, he documented self-confident young people dancing and partying; in his portrait studio, he photographed cosmopolitan citizens from all walks of life. The sitters in his intimate series “Vues de Dos” either turn away from the camera or glance back, returning the viewers’ gaze without compromising their agency or autonomy.

1970s

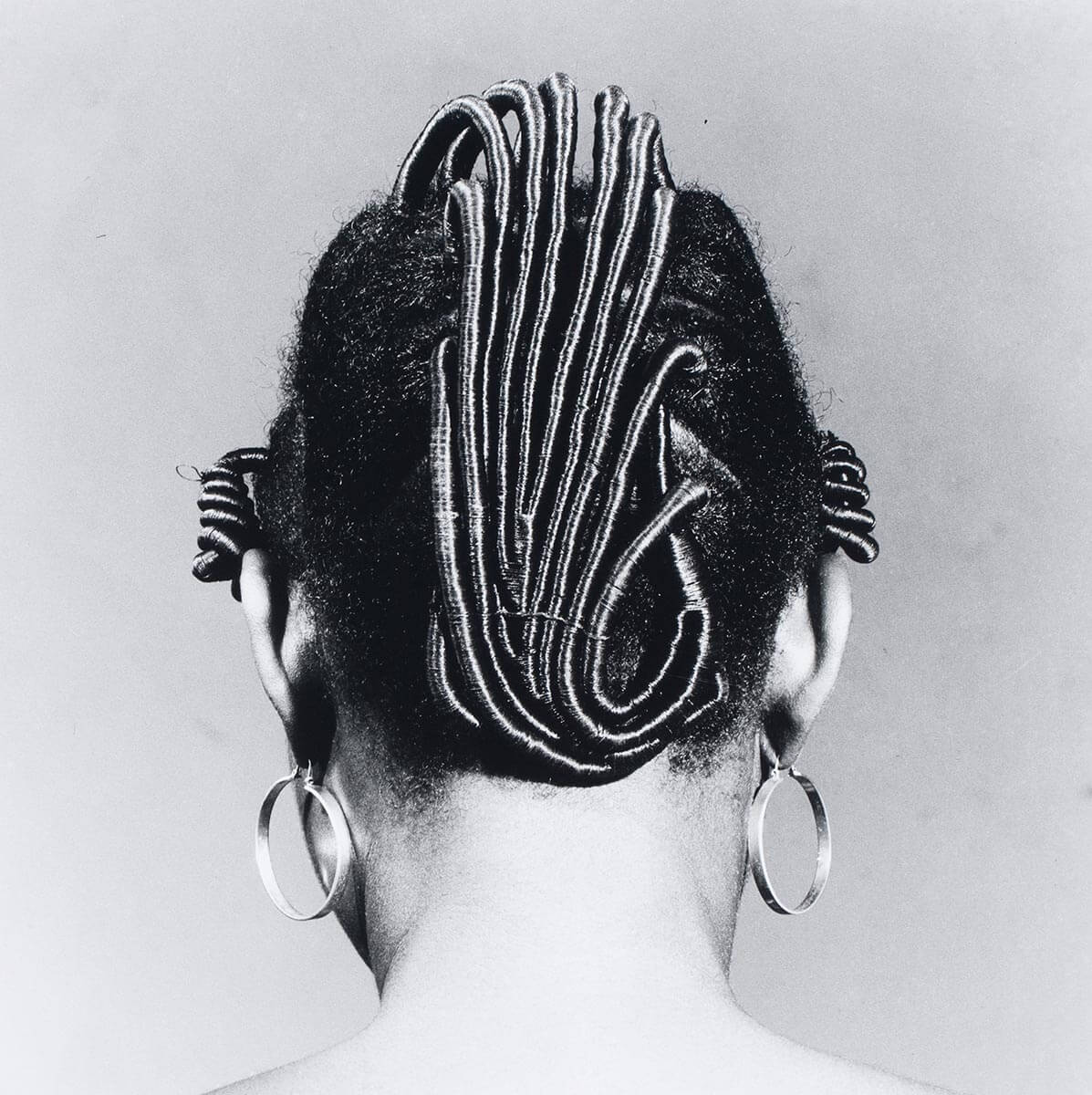

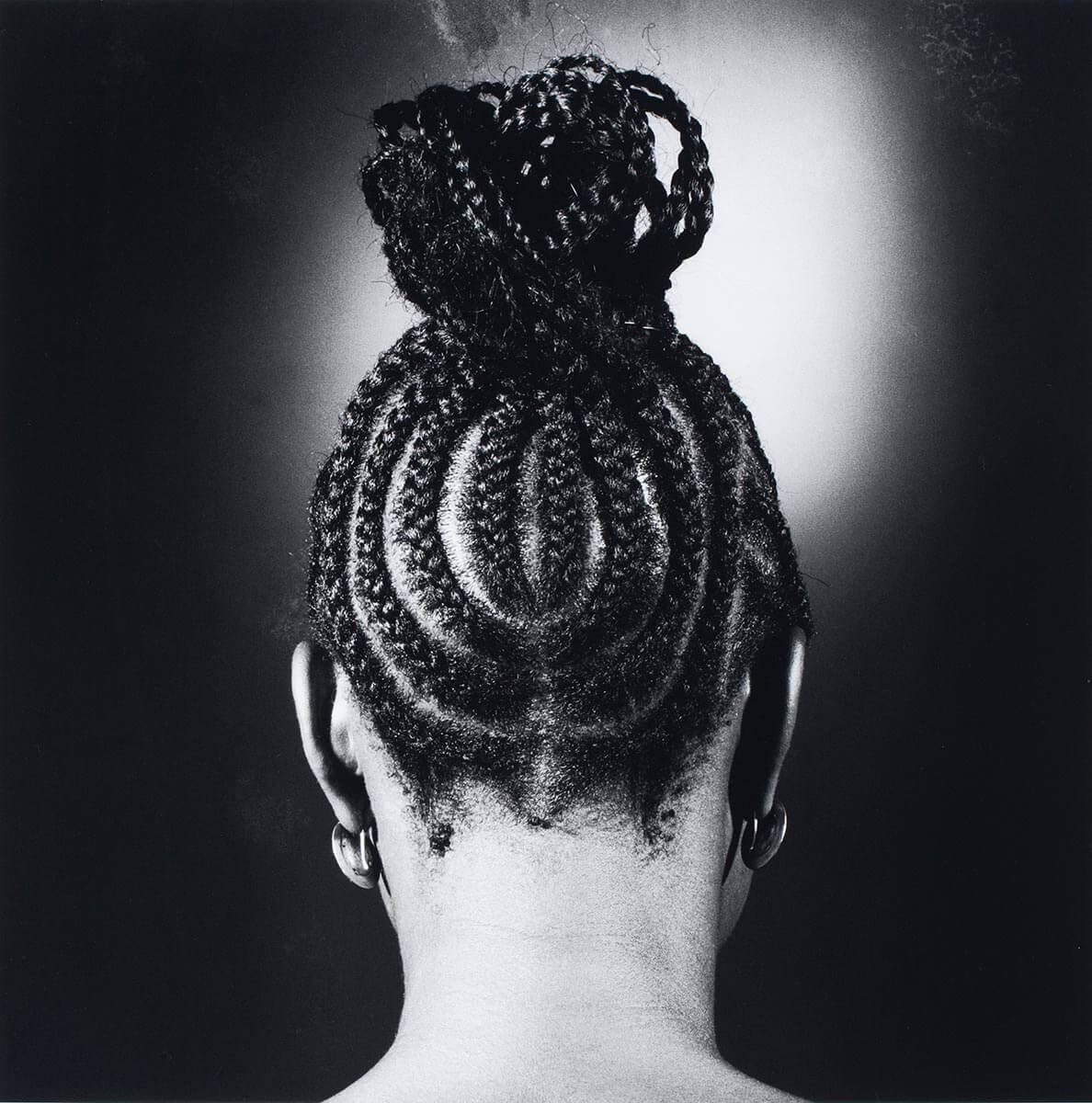

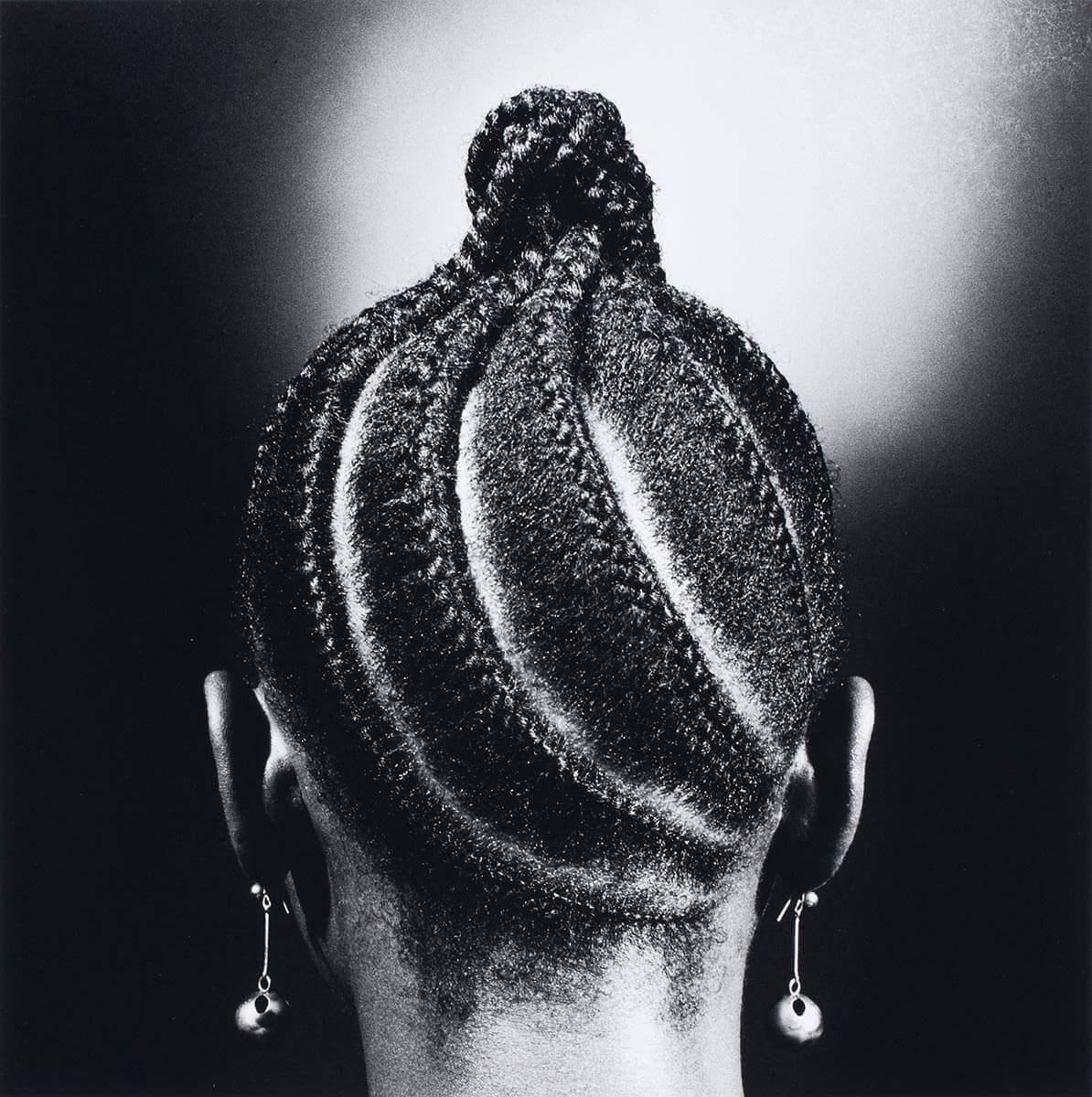

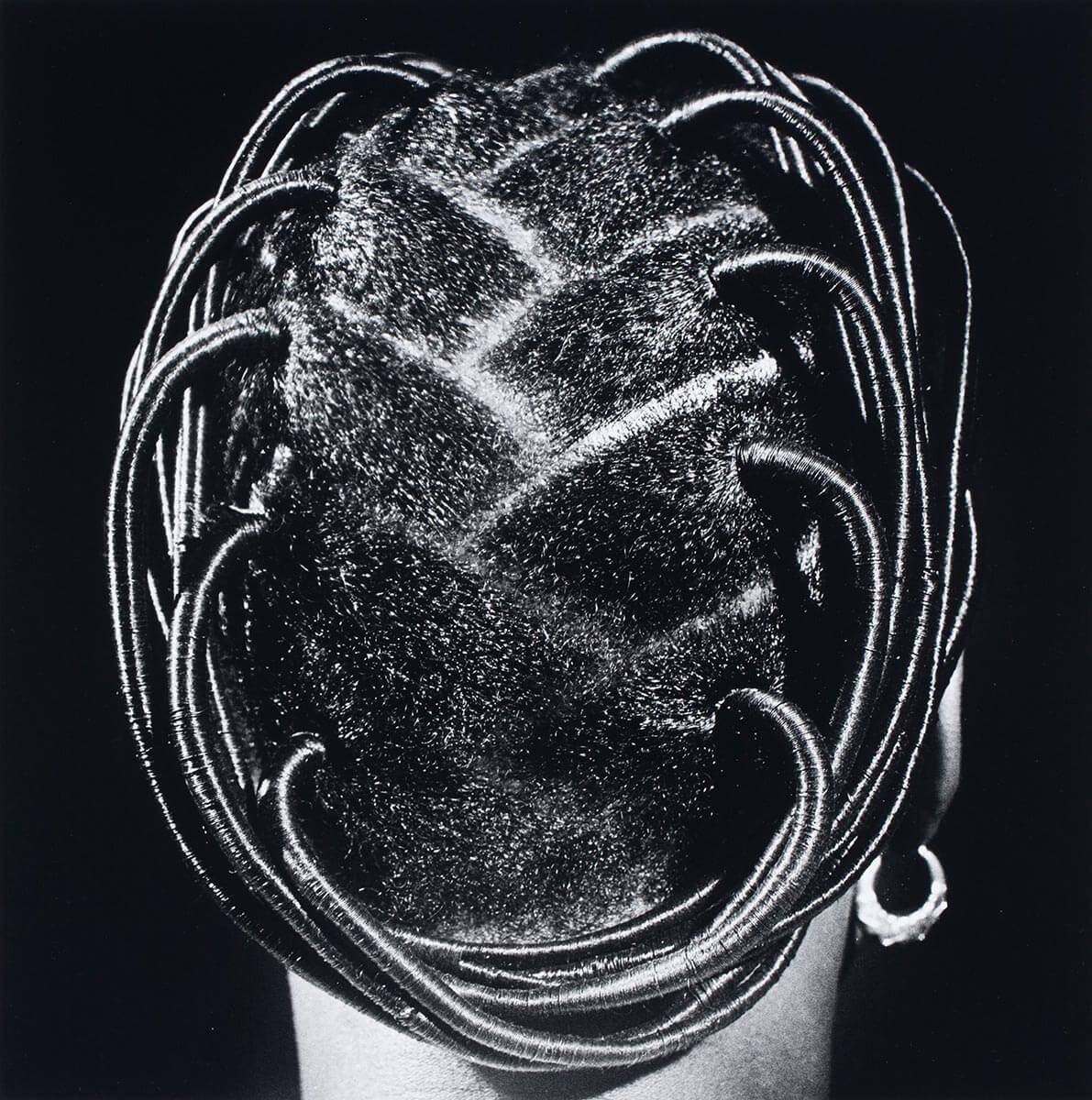

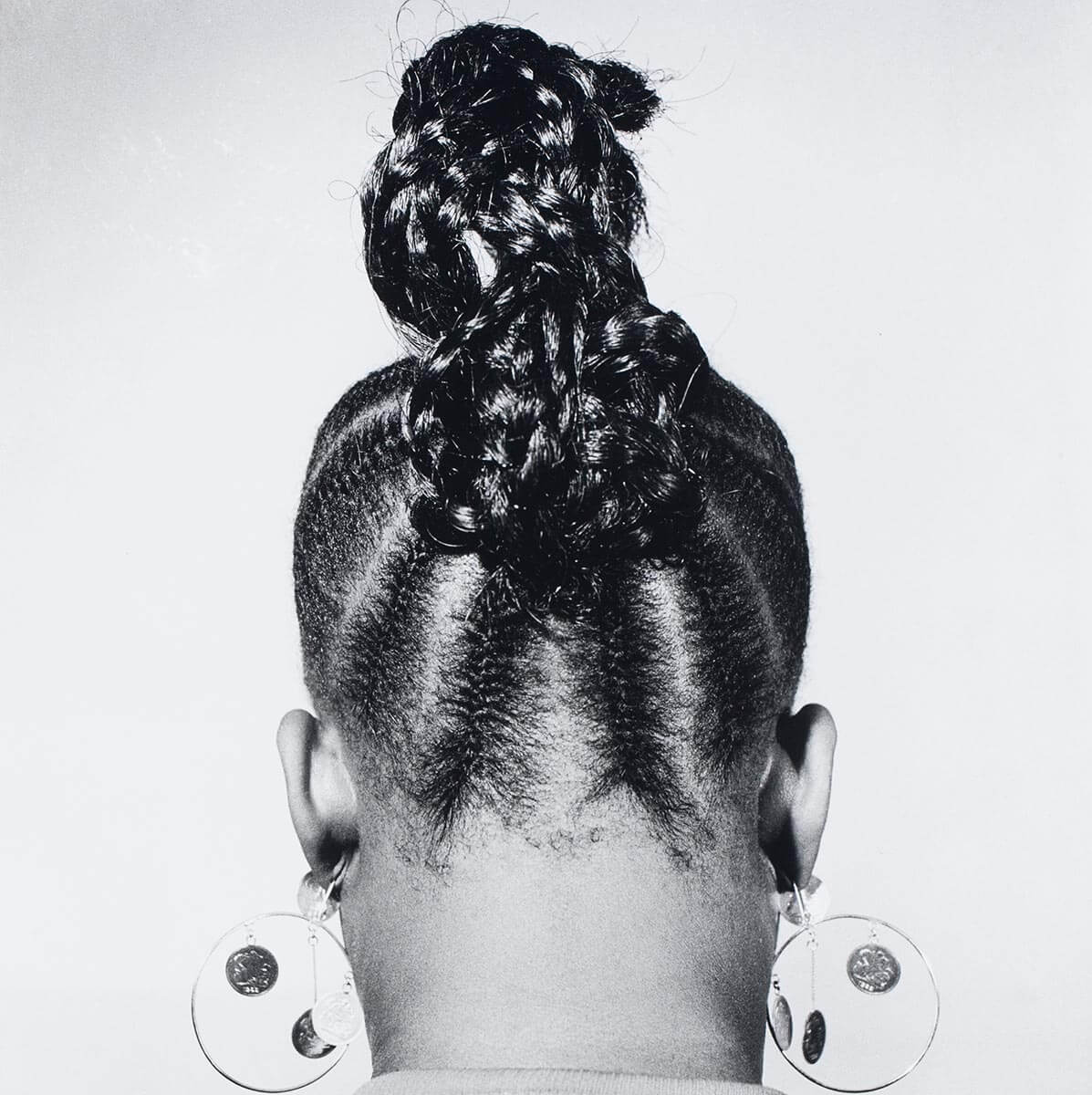

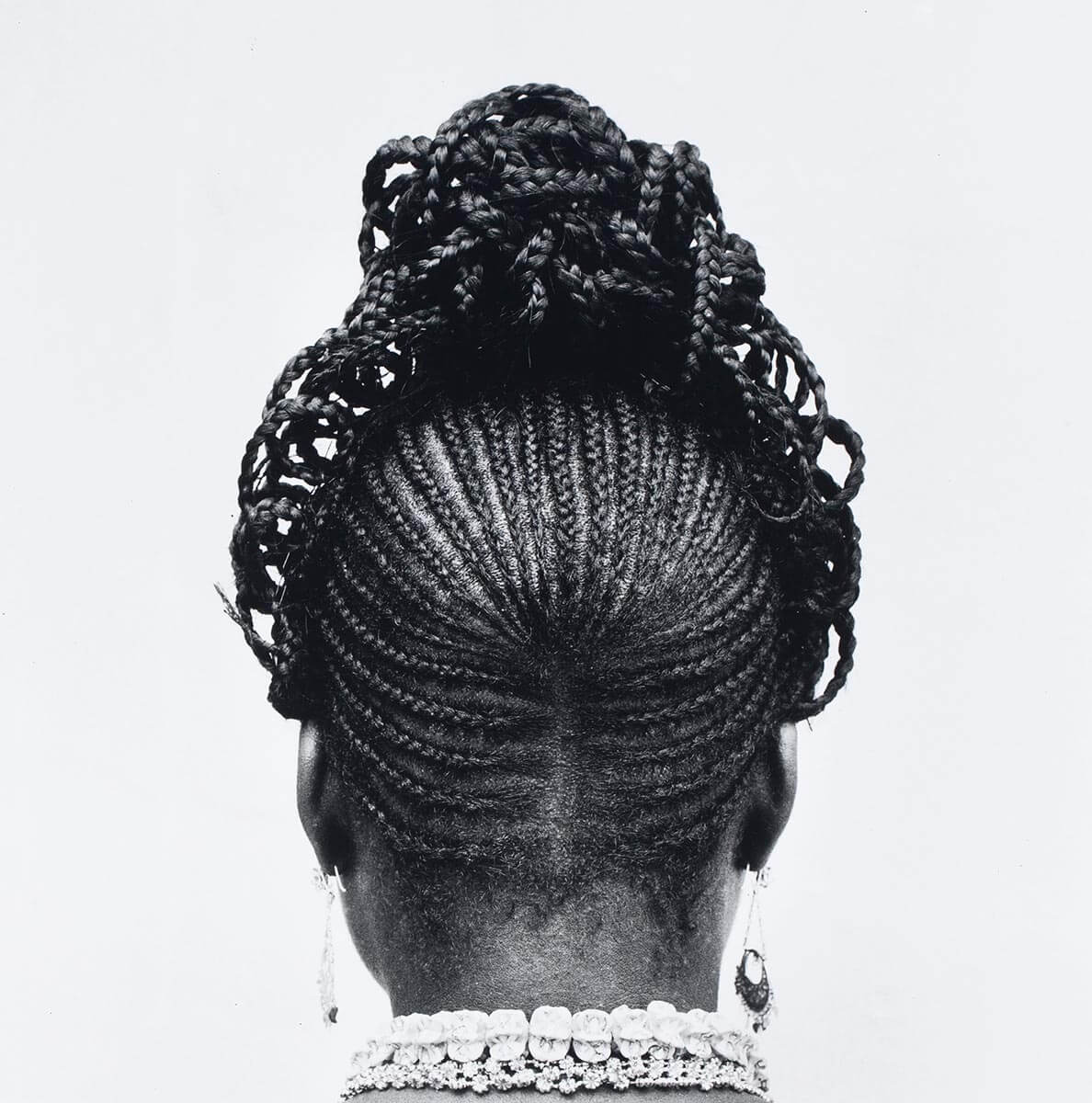

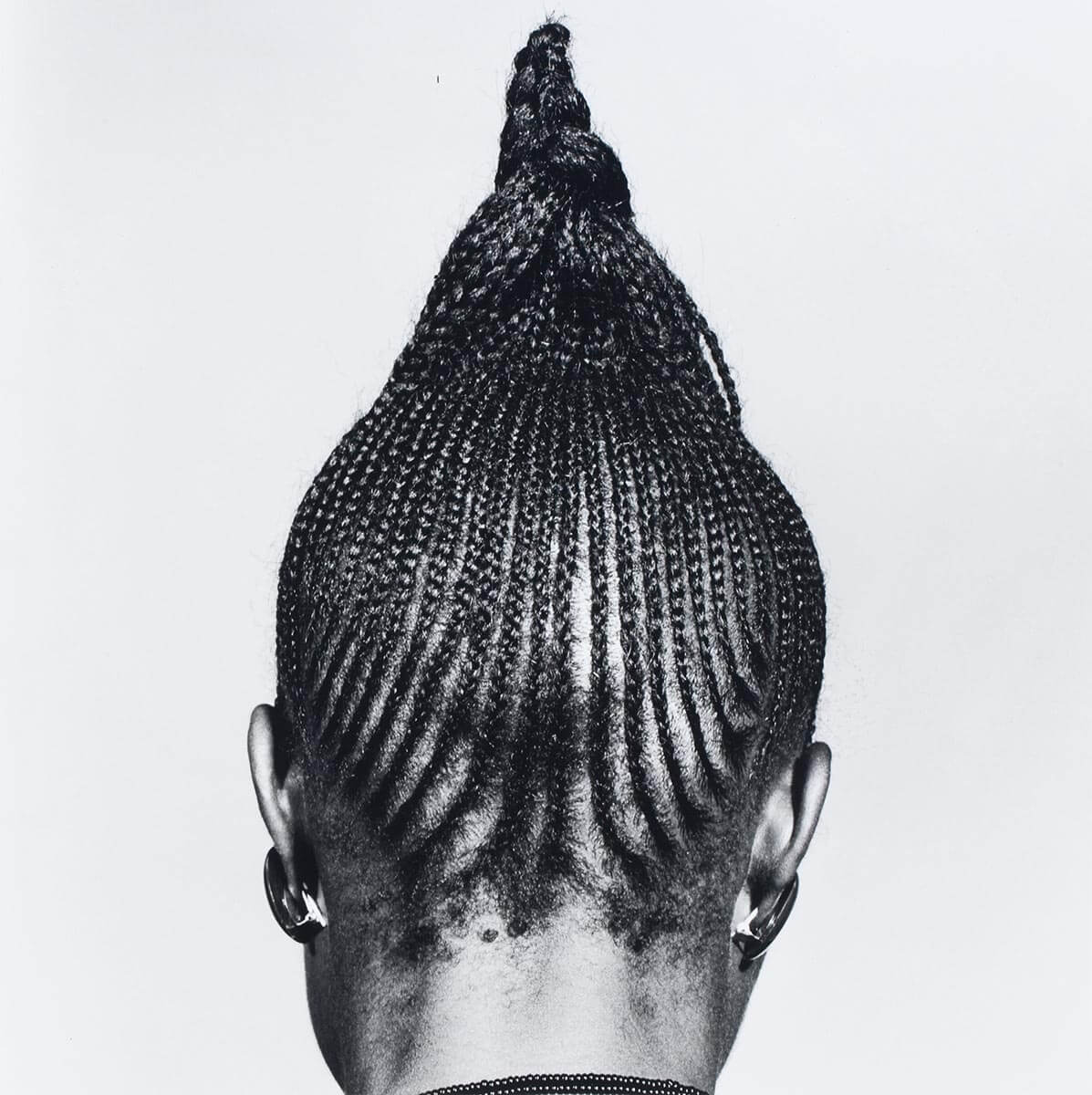

J.D. 'Okhai Ojeikere’s (1930–2014) archive of more than 1000 photographs of Nigerian women’s sculptural hairstyles converge cultural traditions and everyday practices: his typological studies, created during the 1970s, meticulously document the intricate craft of hair braiding as a symbol of collective memory, pride, and national identity.

Contemporaneously in Germany, Bernd (1931–2007) and Hilla Becher (1934–2015) began to methodologically document disused architectural structures and abandoned industrial buildings: water tanks, gas cylinders, and winding towers were ordered according to type, and arranged into grids to emphasize their function, structural form, and original purpose.

Co-curator Maria Müller-Schareck talks about the exhibition’s time capsules

The K21 exhibition “Shifting Dialogues. Photography from The Walther Collection” is conceived in close collaboration with The Walther Collection and supported by curatorial consultant Renée Mussai.

Artur Walther, collector and founder of The Walther Collection, talks about African Photography