Simon Denny speaks to Courtroom Sketch Artist Sharon Gordon

Simon Denny speaks to Courtroom Sketch Artist Sharon Gordon about new commissions made for ‘Mine’ at the K21 in Düsseldorf

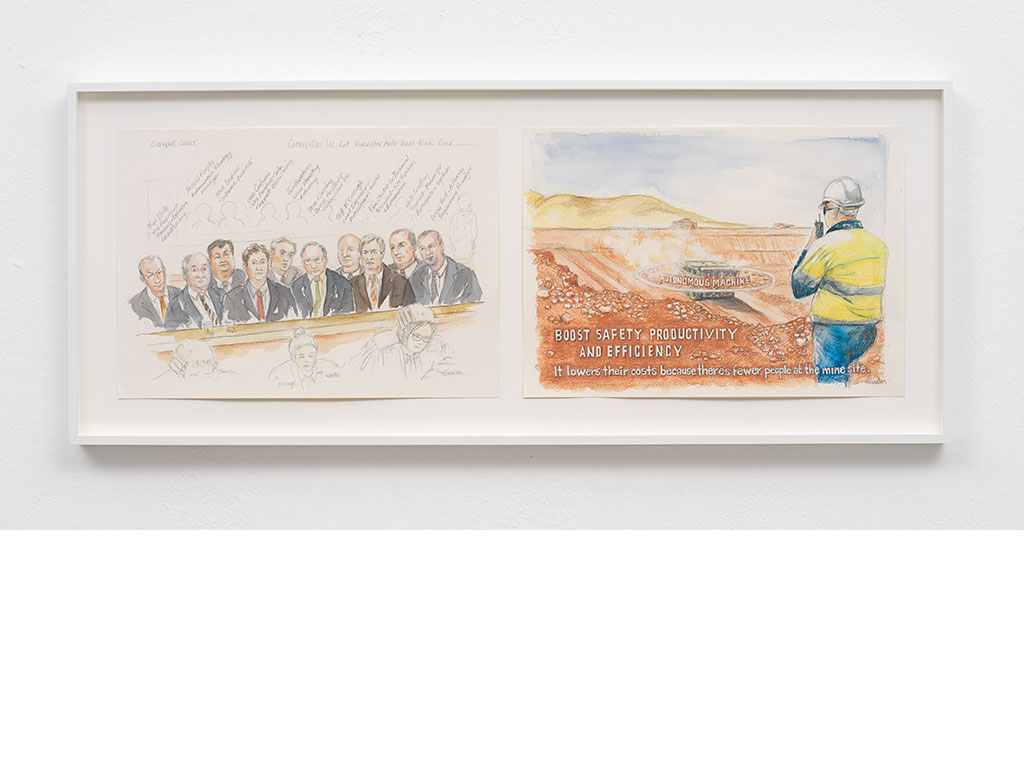

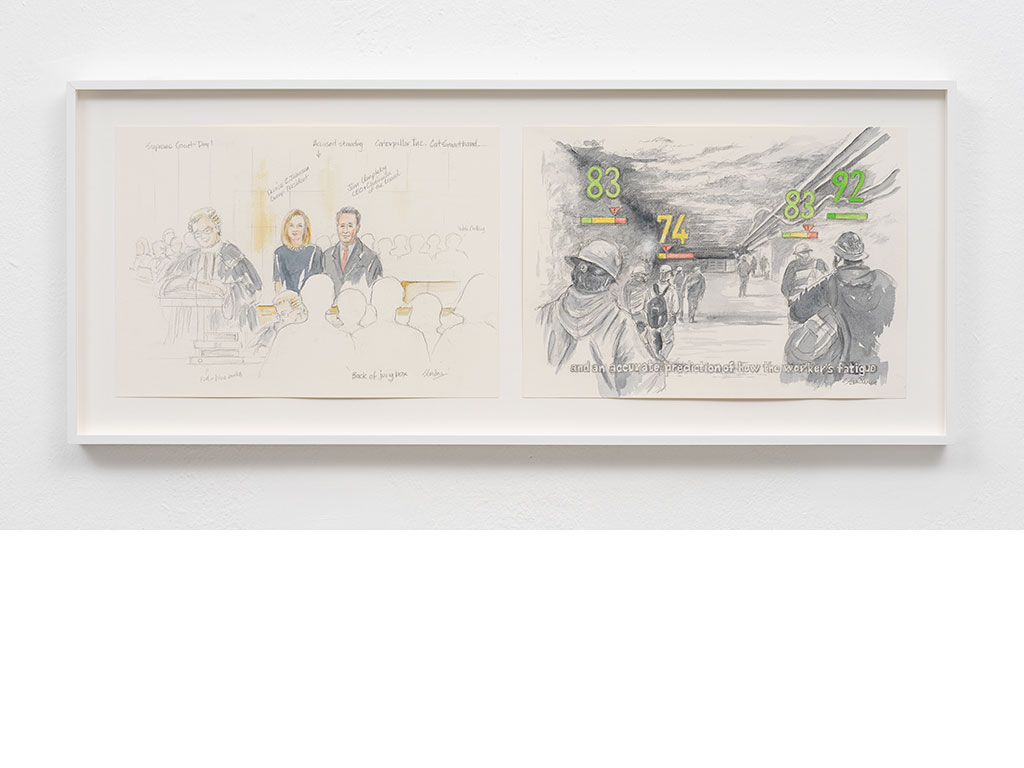

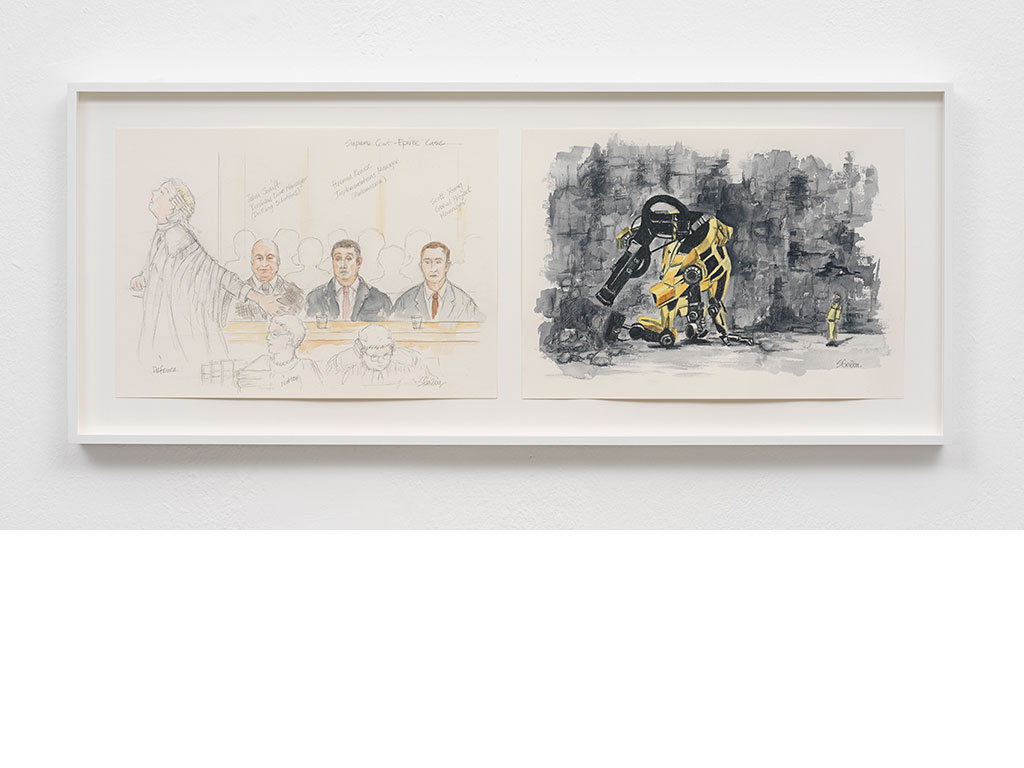

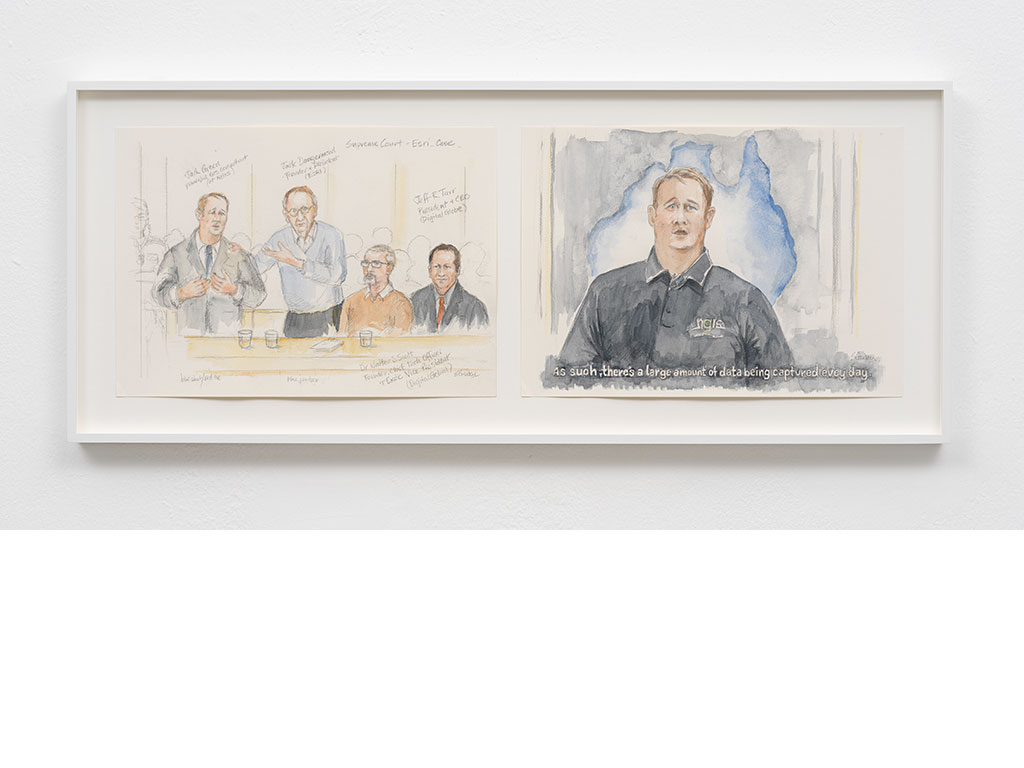

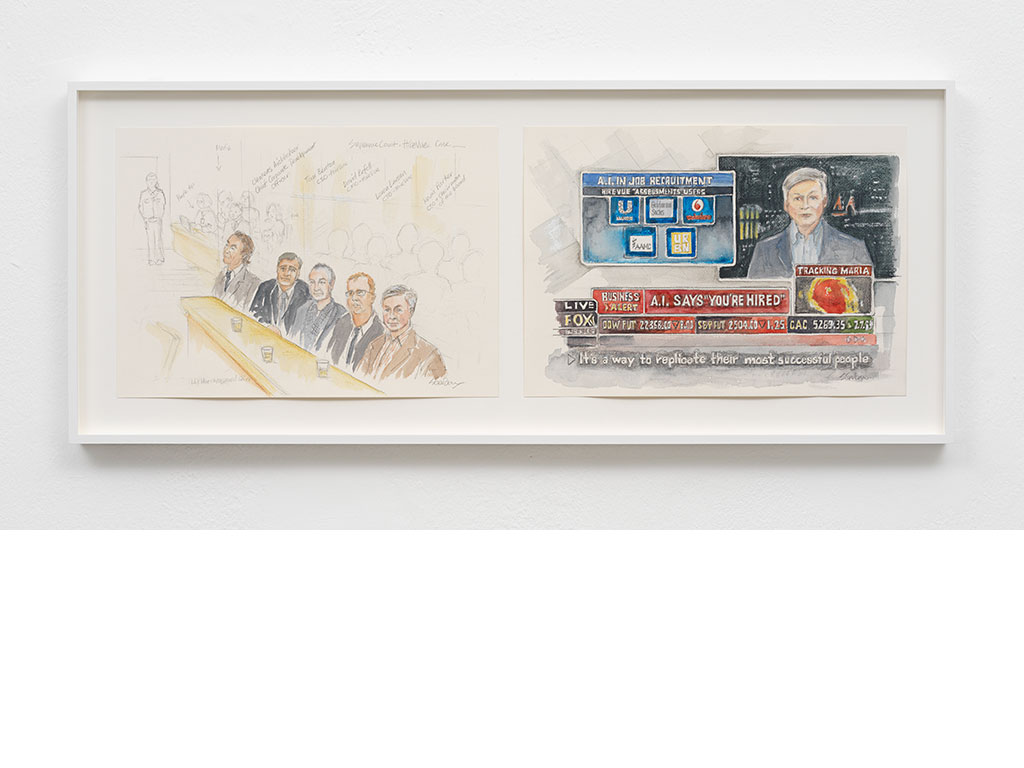

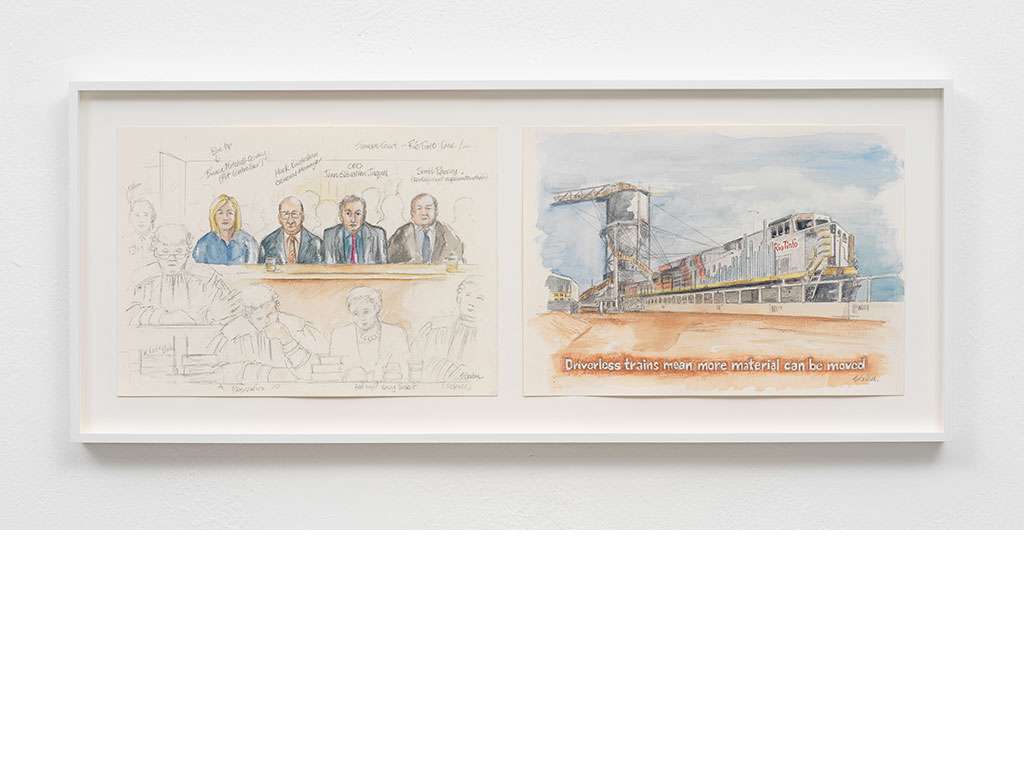

Newly conceived and executed especially for the K21 in Düsseldorf are a series of speculative courtroom drawings made by courtroom sketch artist Sharon Gordon who has been illustrating courtroom trials for 30 years in Brisbane, Australia. Denny commissioned six dyptics – each featuring a drawing imagining a trial of various mining company executives at the Brisbane Supreme Court, and a video still from their respective company’s advertising rendered in “courtroom sketch” style. Here a transcript of a conversation Denny had with Gordon over Zoom in July about their work together.

Simon:

Could you tell me about what you do as a courtroom sketch artist in Brisbane. How did you get started, and what role do you play in the court cases that you work on?

Sharon:

My brother was a cameraman and he worked for the news at a television station.

I had just finished studying and I was asked to come and do court sketching after my brother’s suggestion.There was a need for a court sketcher, and so I went and did an audition in the newsroom. I had to sketch the producer as he walked around the room and I got a likeness so they sent me down to court. This was my first introduction to it.

Simon:

So, it really started from the media side, was it media that were employing you essentially to produce the sketches?

Sharon:

Yes. It was my first job in the media. It wasn't my intention to go into media, but I got in through court sketching, and I went into graphics from there. The very first case that I was sent to, was actually murder trial, and it was quite a difficult murder trial because it was a child. At one stage I actually had to stand in front of the accused outside the courtroom. It was an intense first one.

Simon:

It sounds really intense.

Can you explain the mechanism of being sent to make a court sketch?

It sounds like the media companies will employ you and then you will go into this context as a representative of the media. Do you give or sell your work back to the media to a project and syndicate because they can't take images in the courtroom itself?

Sharon:

Yes, cameras are not allowed into court and sometimes there is no available imagery of the accused. In a lot of cases they actually do have imagery, but it is often that the person who's been accused has actually been in jail for some time before they go to trial, and may look completely different. In some other cases the media actually hadn't been able to capture a shot of them, as their face is often covered up, so the public has no idea what they look like.

It's very interesting for the public to be able to see what these accused look like, because they'll go off to jail and they'll never be seen again. People want to see that, they want to feel that the person is getting what they deserve. That's what I'm capturing in the courtroom.

Simon:

So, you can say that you're really going for a likeness as the main aim when sketching? Are there any other criteria that you think make a good courtroom sketch?

Sharon:

Yes, you're capturing more than just that likeness. You're capturing the whole mood of the courtroom, which I think is really important. Generally you get paid as a court sketcher to go and do one sketch, which is a sketch of that person who's accused because they don't have any images of them. It would usually be a Supreme Court Case these days, as they're the newsworthy cases. If it's a longer trial or if you've got enough time, it's good to get a few sketches to get a real feel of the room. In most cases, I will actually get the accused and I'll try to get him or her in the scene, because I think it's really important to kind of digest the whole scene, to take a bit of time and then distil it into one picture. This way, you can show what exactly is happening in the courtroom and the real mood of the courtroom. This can be done by capturing all the gestures, all those mannerisms that the barristers and the accused have.

A very good example is one case that I did where the accused actually had been in jail for a couple of years before he went to trial. Before that he was quite a robust man, looked very confident. When he actually entered the courtroom he had lost an awful lot of weight. I don't know whether he was remorseful or if he acted like he was, but he was crying. He was sort of a crumpled man compared to the images that you'd see on TV, and I really wanted to capture that.

There was a moment when he stood up, as he was being spoken to by the judge, and he was folding his arms in this very strange way. He had a very strange posture. I thought, that's the moment that I want to get, because it was so unusual and nobody would have known that except for the people who were in that court.

It was a very emotional scene; he was standing in the dock, which is right in front of the public gallery, while I was in the jury box looking back. I had the same view as the judge looking at him and I could see him standing there with the victim's family behind him.

They were all there – the public gallery was absolutely full of people – and they were all wearing purple. Purple was the victim's favourite colour. The mother even had her hair dyed purple. Nobody could see that except for us in the room.

Simon:

I really get a sense of what it is to capture the feeling of what will be a very fleeting moment, that only a few people are privy to, it seems important for a public narrative and understanding of what's going on in those courtrooms. With the commissioning process I engaged you in, what I asked you to do was slightly unusual in the fact that we were making images of court cases that actually haven't happened and are pretty unlikely to happen. Can you tell me about the work that we did together, and how the drawings I commissioned from you contrast to what you usually do?

Sharon:

The difference when you do a live court sketch, is that you're sitting in the courtroom and you have one person, usually there's only one accused and there's a whole scene of barristers. You have to sort of blend it all into one picture while getting as much of the likeness as you can in a short amount of time. With your pictures, they were screen grabs and all sorts of pictures that were sourced from different places. I had to imagine them into scenes that I was very used to sketching. That part was easy because I knew what the courtroom looked like. I knew how I could fit them all in and where they would actually sit if they were there.

I wanted it to look as authentic as possible, so I had to put them in suits and take their smiles off their faces. Other times I had to turn or imagine their faces entirely. Then, there was a perspective thing, because you're working from your memory, so you have to imagine the perspective, whereas when you're looking at something real, you can see the perspective. You can look at things as blocks and just condense it that way. When I can't look at things I struggle drawing them from what they are, like a person's face, a room or a perspective. I tend to break it up into shapes and that makes it easier for me to get it right. The way we worked together was great. First we started with a test and I just did a sketch from a video grab. You gave me all of the pictures and I did rough layouts of how I thought they would work, followed by just rough drawings. We started the first sketch, and we went back and forth about details and different options. You showed me some of the things that you liked and I showed you some of the sketches I'd done in the past. You decided that you wanted to have the names written and sketched around them which is something I wouldn't normally leave on a sketch. Then, I went to the drawing level of putting a bit more detail in, to get the likeness of the different people in the scenes and eventually coloured them all up.

Simon:

I wanted the sketches to do the same thing that they usually do for viewers in a way.

To put you in a room and allow you to imagine what might go on in a situation that you're not party to, that you're not present for. I think that's a really interesting connection between a real court sketch that you usually do and this commission. They're both about imagining situations that are not for everybody's eyes. It is a really strong part of what they produce. In a sense, all courtroom sketches are trying to give you a sense of the urgency of the justice that is supposedly being served in those contexts. I think it is a really amazing thing, as it is often about triggering an imagination and communicating a certain understanding of a situation through drawing.

Sharon:

Yes, and the public wants to see that person in court, they want to see whether they're remorseful.

Simon:

You talk about how carrying emotions is really a part of what courtroom sketches do. I think for me, in the speculative drawings you’ve made, it is so compelling to see the emotions that mining executives might have, should they be in these situations, made visible. It’s a kind of hopeful projection of accountability.

Sharon:

The other thing was the other group of sketches that were from stills, the video stills, which you comissioned alongside the more conventional courtroom sketches. I had to look at these in a different way because they weren't court sketches, but I wanted to keep them authentic so I treated them as such.

Simon:

So it's like using the style or the hand of the courtroom sketch, the manner with which you would usually paint a courtroom sketch but then applying it to a video still of advertising produced by these mining companies.

Sharon:

Right – especially with drawing graphic text overlays from the advertising.

Text was really difficult because it was text that had been super-ed on with a drop shadow and then multiple layers. Translating that into a courtroom sketch watercolour was a challenge.

Simon:

It’s interesting, because you're somebody who's worked, not only as a courtroom sketch artist, but also as somebody who produced graphics for television. I find that interesting, for you to use the tools of one part of your artistic capabilities to execute another.

Sharon:

I've spent many years making those videos, so to actually sketch the video was a little strange. That reminded me of doing storyboarding by hand.

Simon:

It’s a storyboard for a video that's already happened, sitting beside a sketch of a courtroom trial that has never happened.